Surgical Prehabilitation Toolkit for Healthcare Providers

Prehabilitation and optimization are crucial strategies for enhancing patient health before surgery, thereby reducing the risk of postoperative complications. The presurgical period represents a window of opportunity to boost and optimize the health of an individual, providing a compensatory buffer for the imminent reduction in physiological reserve post-surgery.

Prehabilitation is a proactive approach that focuses on improving patients' physical and psychological resilience through interventions such as exercise, nutrition, and psychological preparation. Optimization centers on improving patients’ medical conditions prior to surgery such as managing comorbidities, adjusting medications, and conducting health screenings. Both strategies are vital for expediting recovery, improving patient experiences and outcomes, and reducing healthcare system costs.

Surgical Patient Optimization Collaborative

Following on the success of the 2015-16 Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Collaborative, the Surgical Patient Optimization Collaborative (SPOC) launched in 2019 with 14 sites and expanded with another 13 sites in 2022, to include a total of 27 sites. The collaboratives provided system change strategies, funding support, and shared learning to interdisciplinary teams. Through SPOC 1.0 and 2.0, prehabilitation programs have been established in more than 50% of hospitals performing surgery in BC, demonstrating the benefits of prehabilitation to surgical patients, providers, and the healthcare system within the BC surgical landscape.

The Surgical Prehabilitation Toolkit

The Surgical Prehabilitation Toolkit was originally created in 2019 by the BC Surgical Optimization Working Group and vetted by 15 provincial sites involved in the Surgical Patient Optimization Collaborative (SPOC). Through 2024, the BC Prehabilitation Working Group reviewed and updated the toolkit, adding clinical context, actionable recommendations and screening tool recommendations based on current evidence-based guidelines.

The updates reflect valuable feedback from clinicians within the collaborative and insights from field experts, aimed at enhancing the usability of clinical component pathways. These revisions focus on making the pathways more actionable and practical for providers, while also adding new components that address emerging needs and best practices identified through ongoing engagement around prehabilitation.

The toolkit includes clinical context for each clinical component and actionable recommendations for prehabilitation and optimization that may prove useful for health care providers looking to prehabilitate patients before surgery. This toolkit is not meant to dictate the practice of clinicians, rather to provide options that are available to both providers and patients throughout British Columbia. Clinicians are encouraged to use the toolkit at their own discretion based on the best interest of the patient.

A pdf version of the toolkit can be accessed by clicking on the image below or each component can be explored through the menu options to the left or below.

Perioperative Care Alignment and Digital Screening (PCADS)

While SPOC and other research has demonstrated the positive impact of prehabilitation and optimization, typical pre-surgical journeys offer limited opportunity for prehab in the time leading up to surgery due to tight timelines and limited resources. A digital pre-surgical screening workflow has been identified as a critical piece to support prehabilitation and optimization workflows to improve the surgical system of care.

The Perioperative Care Alignment and Digital Screening (PCADS) project (2023-2024), developed a standardized Pre-Surgical Risk Assessment and Triage Tool (PRATT) to identify high-risk patients early in their preoperative wait time and provide standardized evidence-based recommendations for timely interventions like prehabilitation and optimization.

The PRATT is designed to collect patient health information and provide tailored recommendations in a streamlined manner early in the surgical timeline, allowing more time for patients to receive prehabilitation and optimization to improve their health prior to surgery. The clinical output includes:

- Validated perioperative risk scores

- Preoperative medication management recommendations

- Preoperative investigation recommendations

- Preoperative anesthesia consult recommendations

- Pre-Admission Clinic (PAC) nursing actions

- Flagged areas for prehabilitation and optimization prior to surgery

The PRATT currently exists as a database of patient questions and clinical output logic designed to be implemented digitally and integrate seamlessly with the recommendations included in the prehabilitation toolkit. The full PCADS report including the PRATT clinical content is available to any practitioners in British Columbia to incorporate into their prehabilitation workflows via the link below.

PCADS Final Report with PRATT Clinical Content

For a full list of contributors to the Prehabilitation Toolkit and PRATT, please click HERE.

Legal Disclaimer

We try very hard to keep this information accurate and up-to-date, but we cannot guarantee this. This information is intended as a resource and general guidance and is not meant to dictate the practice of clinicians. Clinicians are encourage to use the information at their own discretion based on the best interest of the patient. It cannot be used for any commercial or business purpose. Although we make reasonable efforts to ensure the accuracy of the information in these resources, we make no representations, warranties or guarantees, whether express or implied, that the information is accurate, complete or up to date. We do not exclude or limit in any way our liability to you where it would be unlawful to do so.

© 2025 Specialists Services Committee

This information may be copied for the purpose of producing information materials. Please quote this original source. If you wish to use part of this information in another publication, suitable acknowledgement must be given and the logos, branding, images, and icons removed. For more information, please contact us at sscbc@doctorsofbc.ca.

SSC. (2025). BC Surgical Prehabilitation Toolkit. https://sscbc.ca/surgical-prehab-toolkit

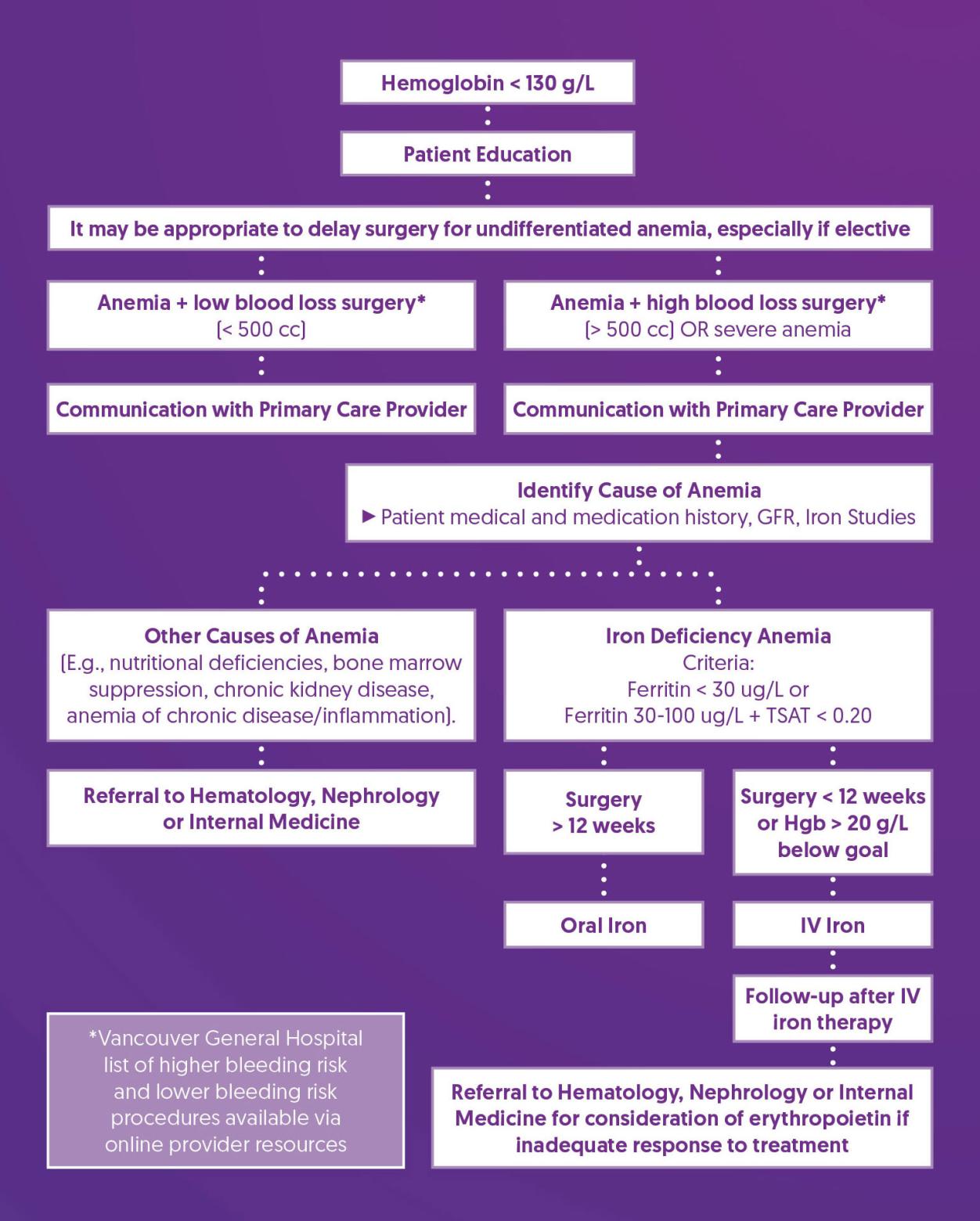

Anemia

Preoperative anemia is common, especially in orthopedic, gynecologic, and colorectal surgical patients. (1,2) “The presence of preoperative anemia, even if mild, has been associated with increased risk of red blood cell (RBC) transfusion and increased morbidity and mortality after surgery. In addition, transfusion of RBCs has been consistently associated with worsened clinical outcomes”. (3)

Screening Tools

Preoperative hemoglobin (Hgb) is recommended for screening based on patient co-morbidities and surgical invasiveness, as per site specific protocols. (3) If a patient is found to be anemic, basic screening for iron deficiency anemia as well as other causes (e.g., chronic kidney disease) is recommended.

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Consider Delaying Surgery |

|

| Communication with Primary Care Provider |

|

| Identify Cause of Anemia |

|

| Treat Iron Deficiency Anemia |

|

| Follow-up After IV Iron Therapy |

|

| Referral to Hematology, Nephrology, or Internal Medicine |

|

References

1. Muñoz, M., Laso-Morales, M. J., Gómez-Ramírez, S., Cadellas, M., Núñez-Matas, M. J., & García-Erce, J. A. (2017). Pre-operative haemoglobin levels and iron status in a large multicentre cohort of patients undergoing major elective surgery. Anaesthesia, 72(7), 826–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.13840

2. Baron, D. M., Hochrieser, H., Posch, M., Metnitz, B., Rhodes, A., Moreno, R. P., Pearse, R. M., Metnitz, P., European Surgical Outcomes Study (EuSOS) group for Trials Groups of European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, & European Society of Anaesthesiology (2014). Preoperative anaemia is associated with poor clinical outcome in non-cardiac surgery patients. British journal of anaesthesia, 113(3), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu098

3. Shander, A., Corwin, H. L., Meier, J., Auerbach, M., Bisbe, E., Blitz, J., Erhard, J., Faraoni, D., Farmer, S. L., Frank, S. M., Girelli, D., Hall, T., Hardy, J. F., Hofmann, A., Lee, C. K., Leung, T. W., Ozawa, S., Sathar, J., Spahn, D. R., Torres, R., … Muñoz, M. (2023). Recommendations From the International Consensus Conference on Anemia Management in Surgical Patients (ICCAMS). Annals of surgery, 277(4), 581–590. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005721

4. BCGuidelines.ca. Iron Deficiency – Diagnosis and Management (2019) Appendix A: Oral Iron Formulations and Adult Doses. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/bc-guidelines/...

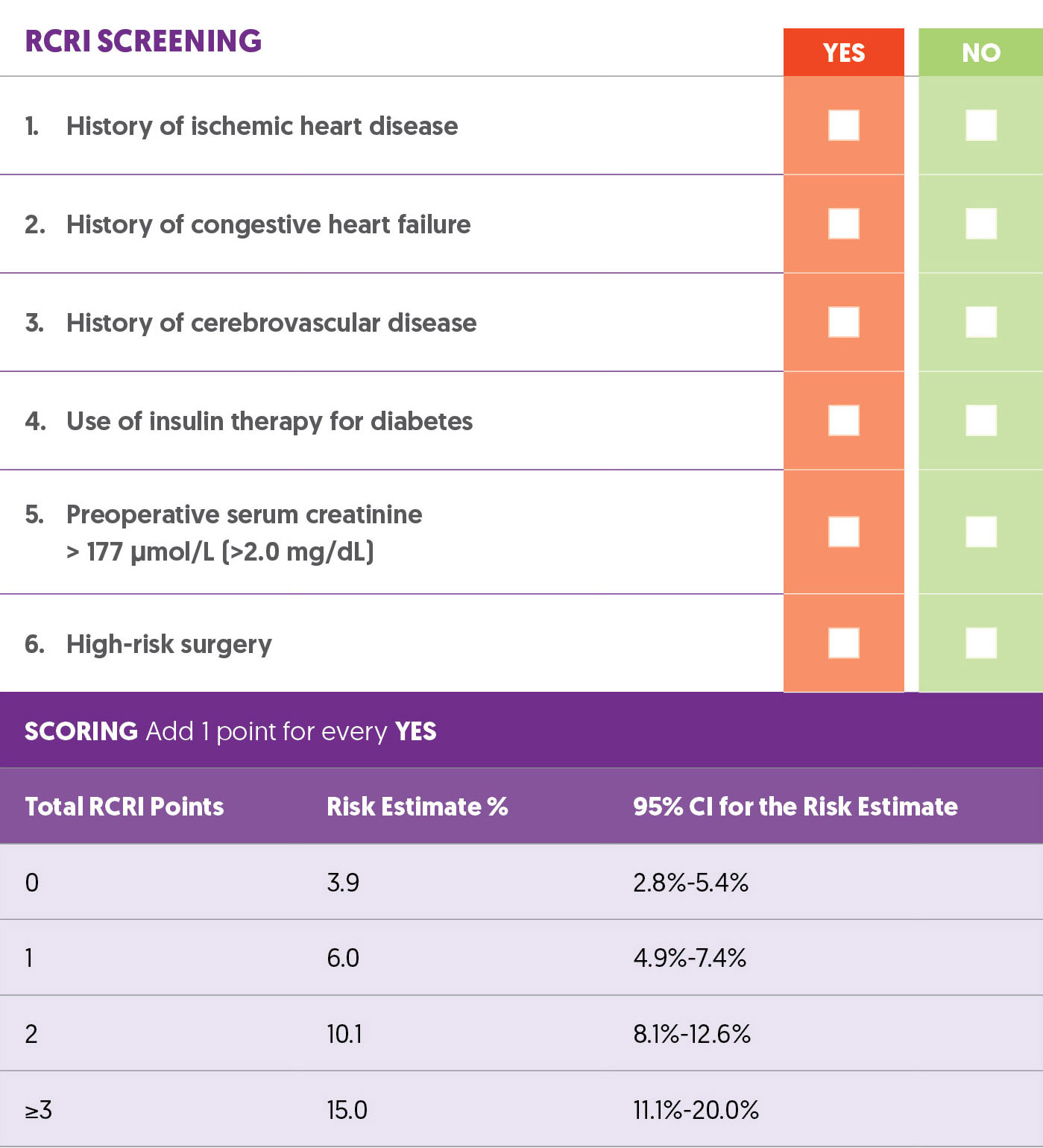

Cardiac Risk

In patients hospitalized for at least one night after non-cardiac surgery, the overall 30-day mortality rate is 1.8% with urgent/emergent surgery being associated with at lease double the risk of elective surgery. (1)

Many of these deaths are linked to cardiac complications (1). Myocardial Injury after Noncardiac Surgery (MINS), indicated by troponin levels exceeding the 99th percentile due to myocardial schema without ischemic features, occurs in 12-24% of cases (2). MINS is associated with a post-operative 30-day mortality rate of 9.8%, compared to 1% for those without it, and increases the risk of major vascular complications such as myocardial infarction and stroke (3,4,5).

Screening Tools

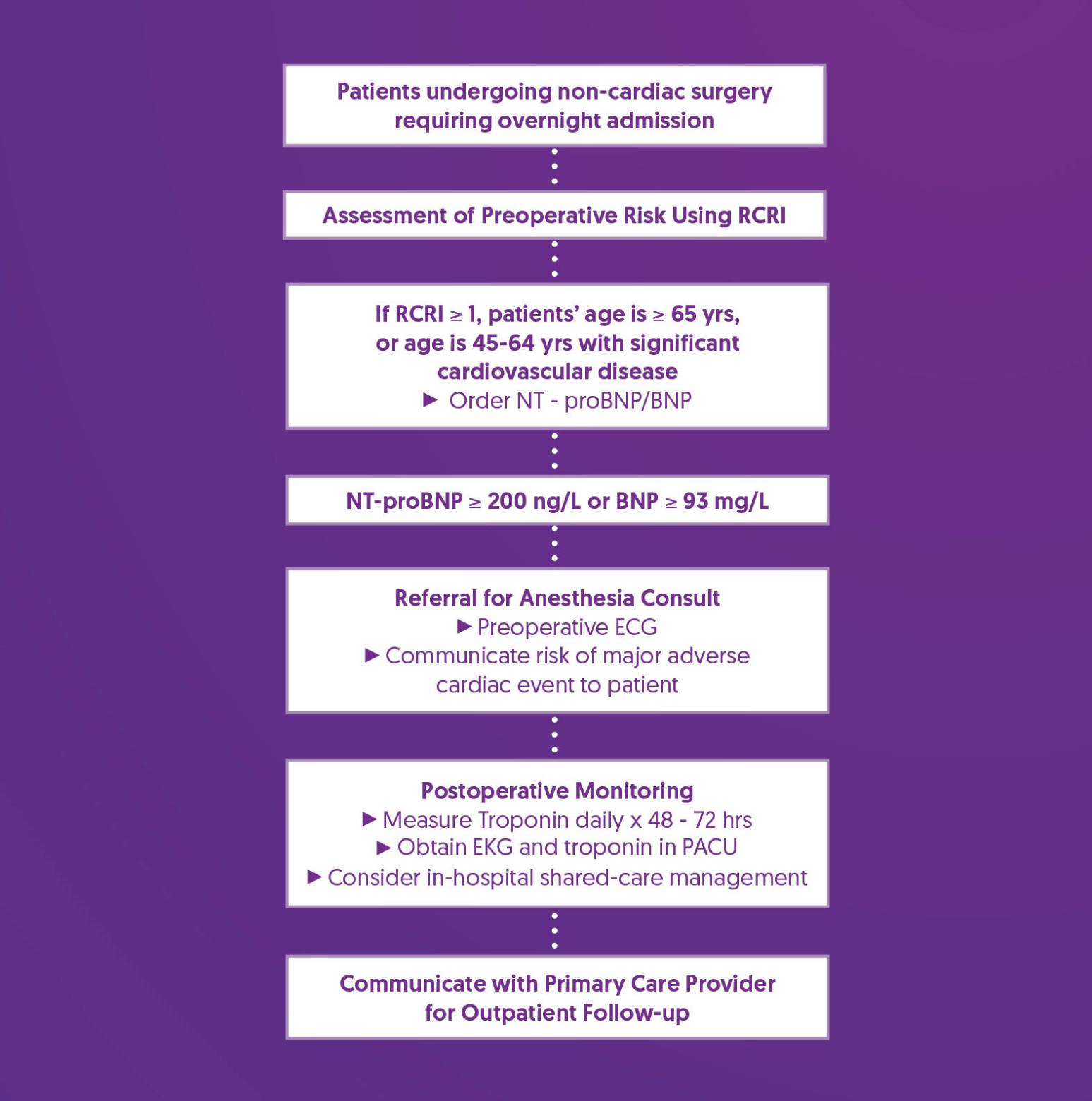

The Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) includes six factors, each worth 1 point (6). A review of 792,740 patients showed that the RCRI has moderate ability to predict major perioperative cardiac complications (7). For patients aged 65 or older, those aged 45-64 with significant cardiovascular disease, or those with an RCRI score ≥ 1, measure NT-proBNP or BNP before noncardiac surgery to improve risk assessment (8).

Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI)

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Order NT-proBNP/BNP |

|

| Referral for Anesthesia Consult |

|

| Postoperative Monitoring |

|

| Communicate with Primary Care Provider for Outpatient Follow-up |

|

References

1. Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators, Spence, J., LeManach, Y., Chan, M. T. V., Wang, C. Y., Sigamani, A., Xavier, D., Pearse, R., Alonso-Coello, P., Garutti, I., Srinathan, S. K., Duceppe, E., Walsh, M., Borges, F. K., Malaga, G., Abraham, V., Faruqui, A., Berwanger, O., Biccard, B. M., Villar, J. C., … Devereaux, P. J. (2019). Association between complications and death within 30 days after noncardiac surgery. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 191(30), E830–E837. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190221

2. Smilowitz, N. R., Redel-Traub, G., Hausvater, A., Armanious, A., Nicholson, J., Puelacher, C., & Berger, J. S. (2019). Myocardial Injury After Noncardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiology in review, 27(6), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0000000000000254

3. Writing Committee for the VISION Study Investigators, Devereaux, P. J., Biccard, B. M., Sigamani, A., Xavier, D., Chan, M. T. V., Srinathan, S. K., Walsh, M., Abraham, V., Pearse, R., Wang, C. Y., Sessler, D. I., Kurz, A., Szczeklik, W., Berwanger, O., Villar, J. C., Malaga, G., Garg, A. X., Chow, C. K., Ackland, G., … Guyatt, G. H. (2017). Association of Postoperative High-Sensitivity Troponin Levels With Myocardial Injury and 30-Day Mortality Among Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. JAMA, 317(16), 1642–1651. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.4360

4. Devereaux, P. J., Duceppe, E., Guyatt, G., Tandon, V., Rodseth, R., Biccard, B. M., Xavier, D., Szczeklik, W., Meyhoff, C. S., Vincent, J., Franzosi, M. G., Srinathan, S. K., Erb, J., Magloire, P., Neary, J., Rao, M., Rahate, P. V., Chaudhry, N. K., Mayosi, B., de Nadal, M., … MANAGE Investigators (2018). Dabigatran in patients with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MANAGE): an international, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 391(10137), 2325–2334. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30832-8

5. Botto, F., Alonso-Coello, P., Chan, M. T., Villar, J. C., Xavier, D., Srinathan, S., Guyatt, G., Cruz, P., Graham, M., Wang, C. Y., Berwanger, O., Pearse, R. M., Biccard, B. M., Abraham, V., Malaga, G., Hillis, G. S., Rodseth, R. N., Cook, D., Polanczyk, C. A., Szczeklik, W., … Vascular events In noncardiac Surgery patIents cOhort evaluatioN VISION Study Investigators (2014). Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a large, international, prospective cohort study establishing diagnostic criteria, characteristics, predictors, and 30-day outcomes. Anesthesiology, 120(3), 564–578.https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000113

6. Lee, T. H., Marcantonio, E. R., Mangione, C. M., Thomas, E. J., Polanczyk, C. A., Cook, E. F., Sugarbaker, D. J., Donaldson, M. C., Poss, R., Ho, K. K., Ludwig, L. E., Pedan, A., & Goldman, L. (1999). Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation, 100(10), 1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1043

7. Ford, M. K., Beattie, W. S., & Wijeysundera, D. N. (2010). Systematic review: prediction of perioperative cardiac complications and mortality by the revised cardiac risk index. Annals of internal medicine, 152(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00007

8. Duceppe, E., Parlow, J., MacDonald, P., Lyons, K., McMullen, M., Srinathan, S., Graham, M., Tandon, V., Styles, K., Bessissow, A., Sessler, D. I., Bryson, G., & Devereaux, P. J. (2017). Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Management for Patients Who Undergo Noncardiac Surgery. The Canadian journal of cardiology, 33(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2016.09.008

Delirium

Postoperative delirium is one of the most common complications following major surgery. While many cases may be preventable, it may affect up to half of older adults and often goes unrecognized. It is associated with increased postoperative complications, length of stay in hospital, non-home discharge, mortality, and healthcare costs, as well as decline in function and cognition. (1-4)

Screening Tools

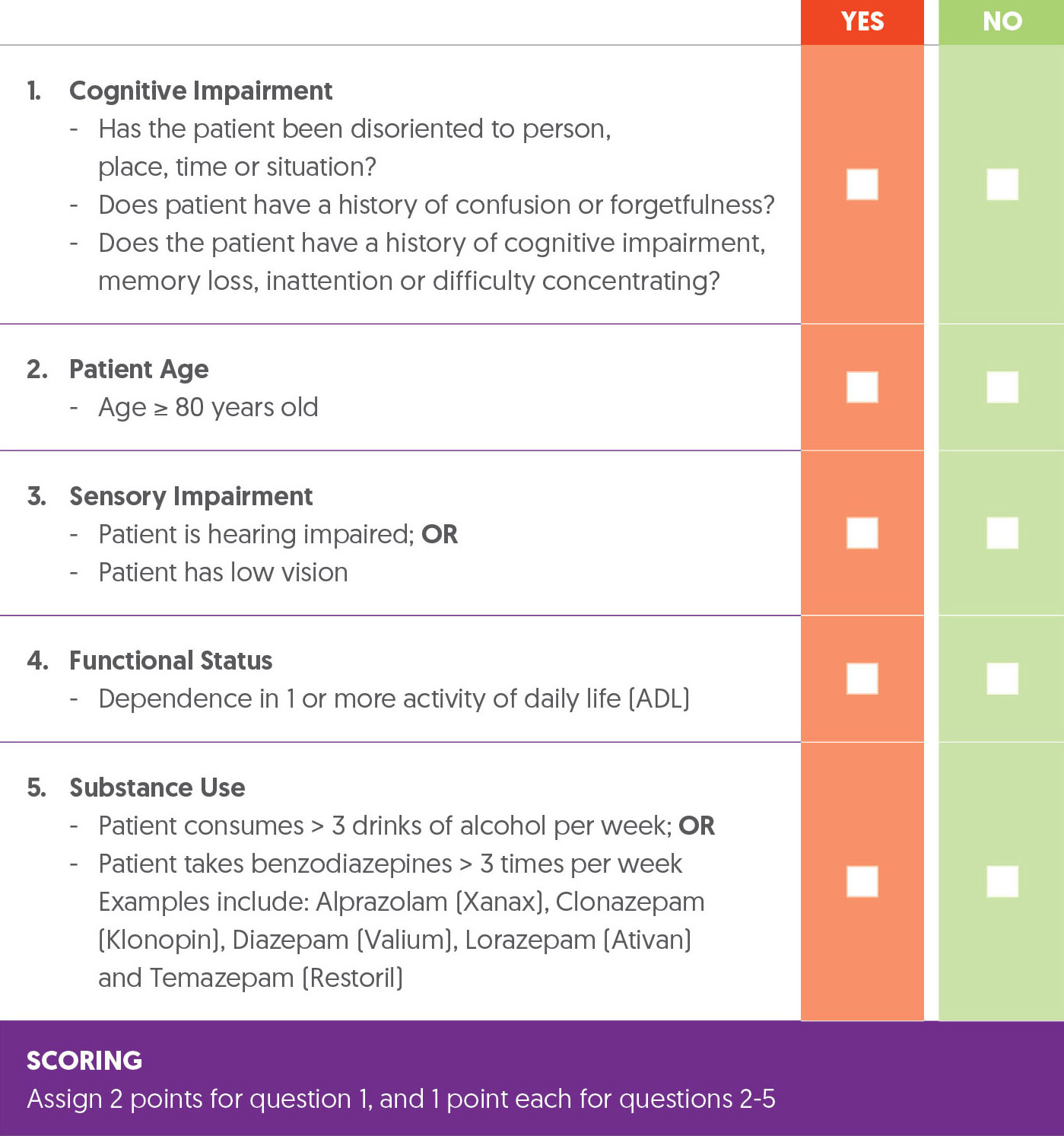

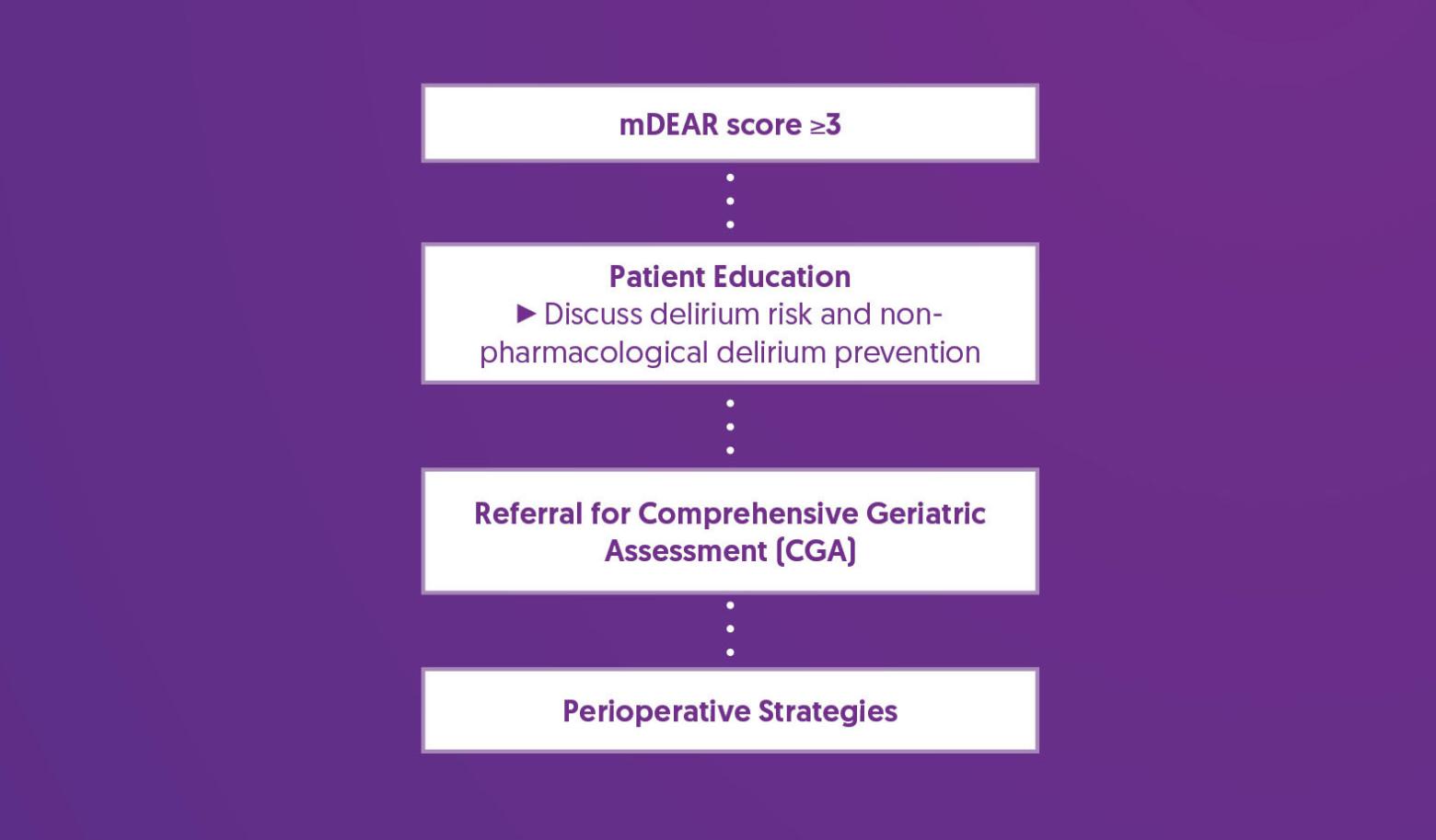

The Delirium Elderly At-Risk (DEAR) instrument has been used to predict postoperative delirium in elective and emergency orthopedic patients based on cognitive impairment, age, functional dependence, sensory impairment, and chronic substance use. “Among arthroplasty patients, having two or more risk factors was associated with an eight-fold increase in the incidence of delirium.” (1) The modified DEAR (mDEAR) uses routinely collected medical record data to assess cognitive impairment instead of the MMSE utilized in the DEAR and attributes 2 points to cognitive impairment and 1 point to each other factor. A patient scoring 3 or more indicates a higher risk of developing delirium. (5)

mDEAR Screening Instrument

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Referral for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) |

|

| Perioperative Strategies |

|

References

1. Freter, S. H. (2005). Predicting post-operative delirium in elective orthopaedic patients: The Delirium Elderly At-Risk (DEAR) instrument. Age and Ageing, 34(2), 169–171. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh245

2. Freter, S., Dunbar, M., Koller, K., MacKnight, C., & Rockwood, K. (2015). Risk of Pre-and Post-Operative Delirium and the Delirium Elderly At Risk (DEAR) Tool in Hip Fracture Patients. Canadian geriatrics journal : CGJ, 18(4), 212–216. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.18.185

3. Zywiel, M. G., Hurley, R. T., Perruccio, A. V., Hancock-Howard, R. L., Coyte, P. C., & Rampersaud, Y. R. (2015). Health economic implications of perioperative delirium in older patients after surgery for a fragility hip fracture. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, 97(10), 829–836. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.N.00724

4. Yan, E., Veitch, M., Saripella, A., Alhamdah, Y., Butris, N., Tang-Wai, D. F., Tartaglia, M. C., Nagappa, M., Englesakis, M., He, D., & Chung, F. (2023). Association between postoperative delirium and adverse outcomes in older surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 90, 111221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2023.111221

5. Meehan, A. J., Gabra, J. N., Whyde, C. (2023). Development and validation of a delirium risk prediction model using a modified version of the Delirium Eldery at Risk (mDEAR) screen in hospitalized patients aged 65 and older: A medical record review. Geriatric Nursing, 51, 150-155.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.03.003

6. Jin, Z., Hu, J., & Ma, D. (2020). Postoperative delirium: perioperative assessment, risk reduction, and management. British journal of anaesthesia, 125(4), 492–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.063

Frailty

Frailty is a clinical state of increased vulnerability due to age-associated decline in physiological reserve, resulting in compromised ability to cope with external everyday or acute stressors. (1) Preoperative frailty is associated with increased postoperative complications, mortality, and longer-term negative outcomes, including falls, lower quality of life, non-home discharge, and prolonged length of stay. (2,3)

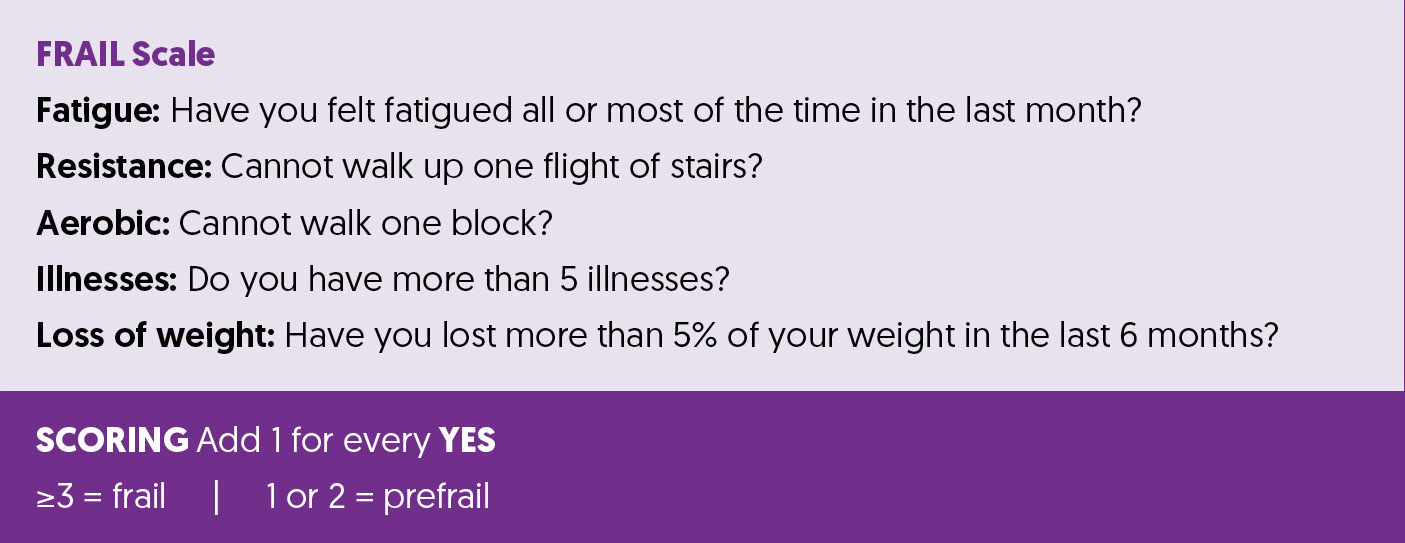

Screening Tools

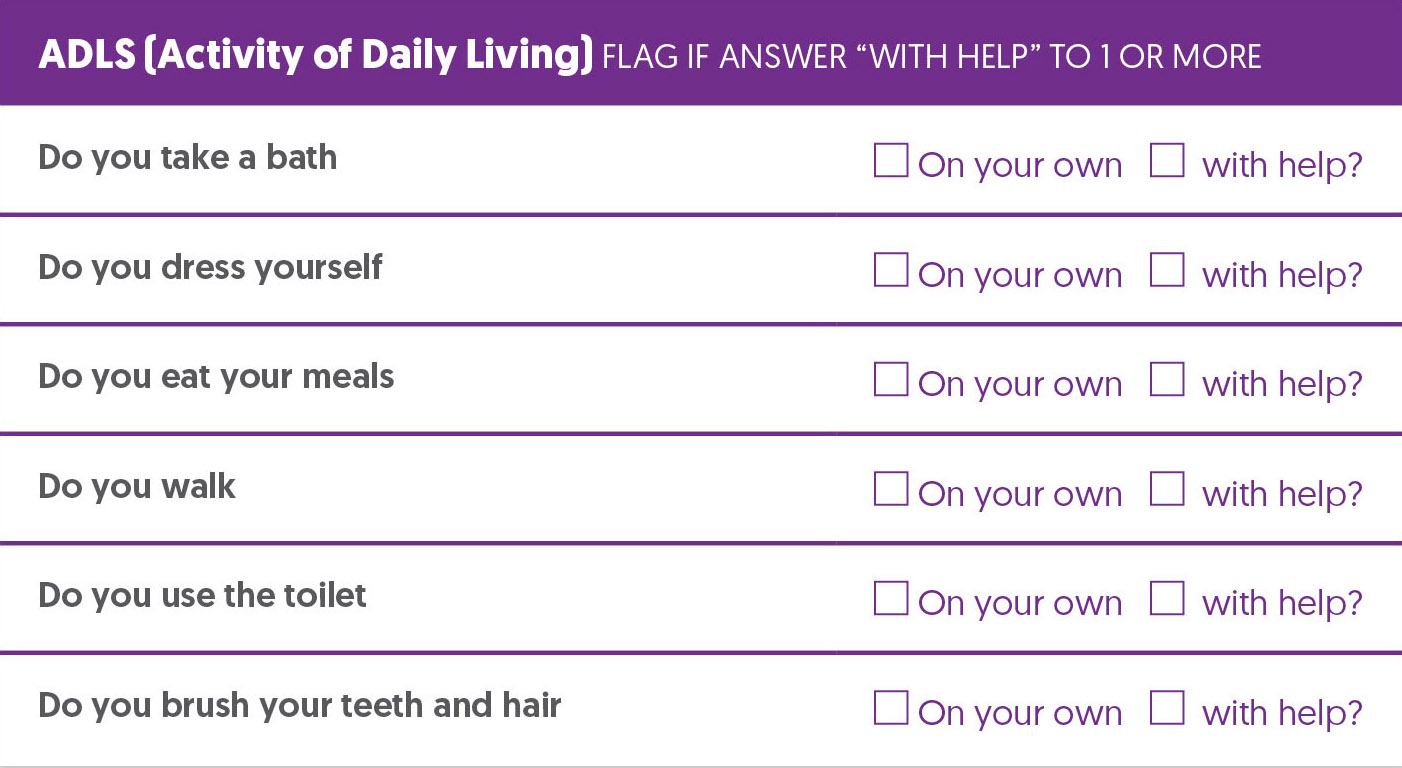

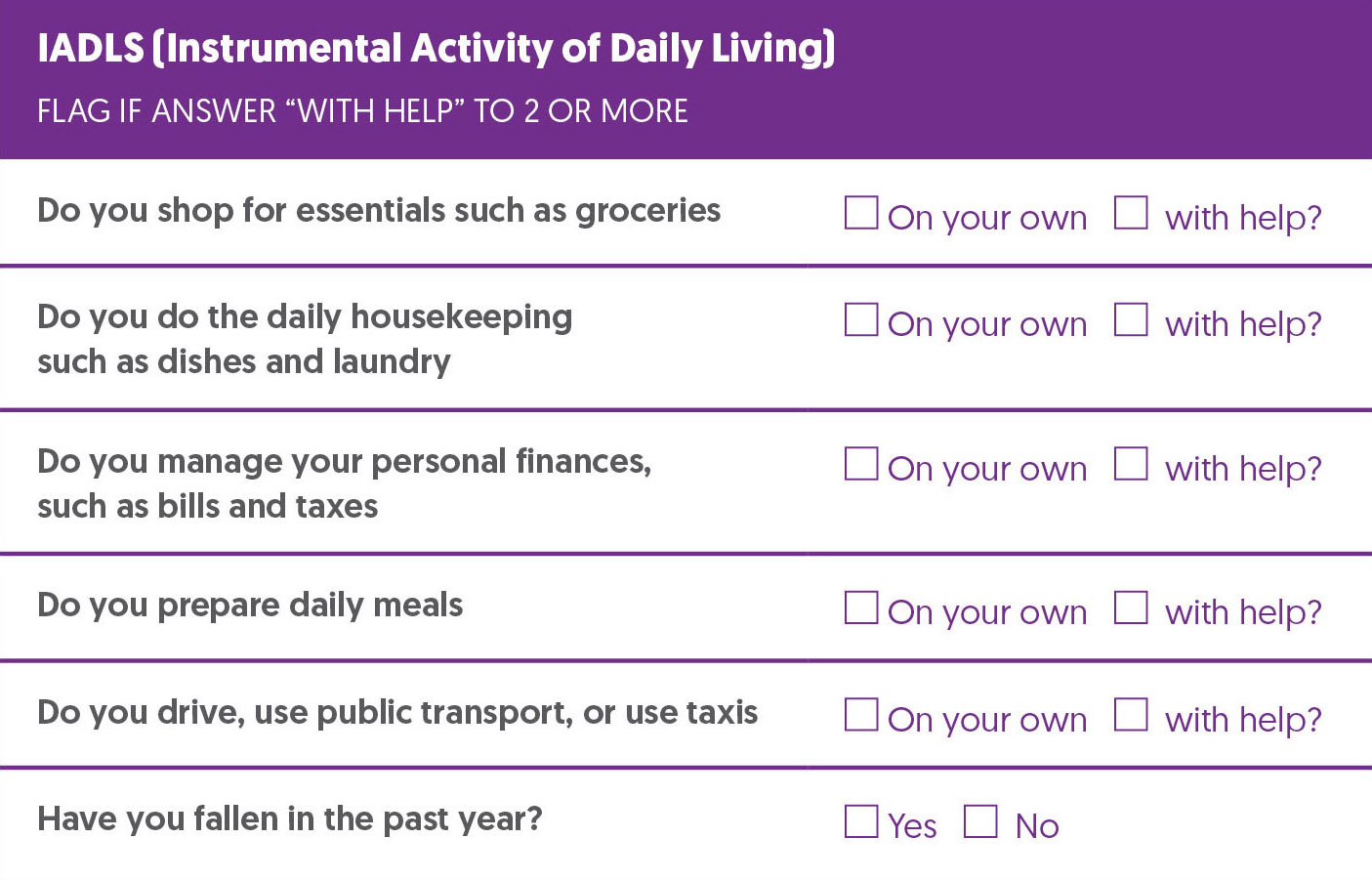

The FRAIL scale has been validated as a preoperative screening tool for frailty and as a predictor of mortality and postoperative complication. (4) Many geriatricians find ADLs and IADLs as a useful adjunct to a screening tool.

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Preoperative Risk Discussion |

|

| Referral for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) |

|

References

1. Fried, L. P., Tangen, C. M., Walston, J., Newman, A. B., Hirsch, C., Gottdiener, J., Seeman, T., Tracy, R., Kop, W. J., Burke, G., McBurnie, M. A., & Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group (2001). Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 56(3), M146–M156. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146

2. Lin, H. S., Watts, J. N., Peel, N. M., & Hubbard, R. E. (2016). Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic review. BMC geriatrics, 16(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0329-8

3. McIsaac, D. I., Aucoin, S. D., Bryson, G. L., Hamilton, G. M., & Lalu, M. M. (2021). Complications as a Mediator of the Perioperative Frailty–Mortality Association. Anesthesiology, 134(4), 577–587. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003699

4. Gong, S., Qian, D., Riazi, S., Chung, F., Englesakis, M., Li, Q., Huszti, E., & Wong, J. (2023). Association Between the FRAIL Scale and Postoperative Complications in Older Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesthesia and analgesia, 136(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006272

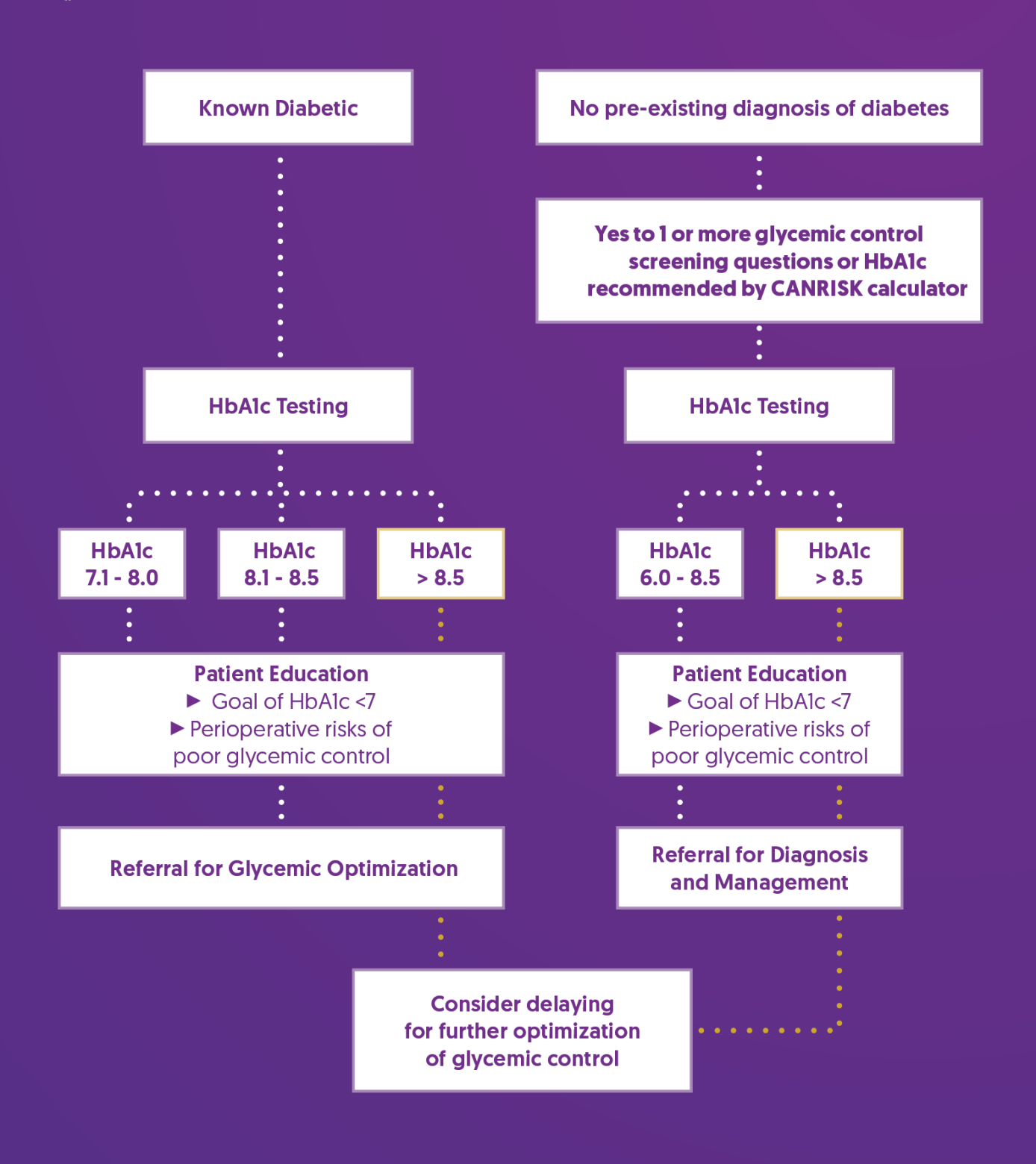

Glycemic Control

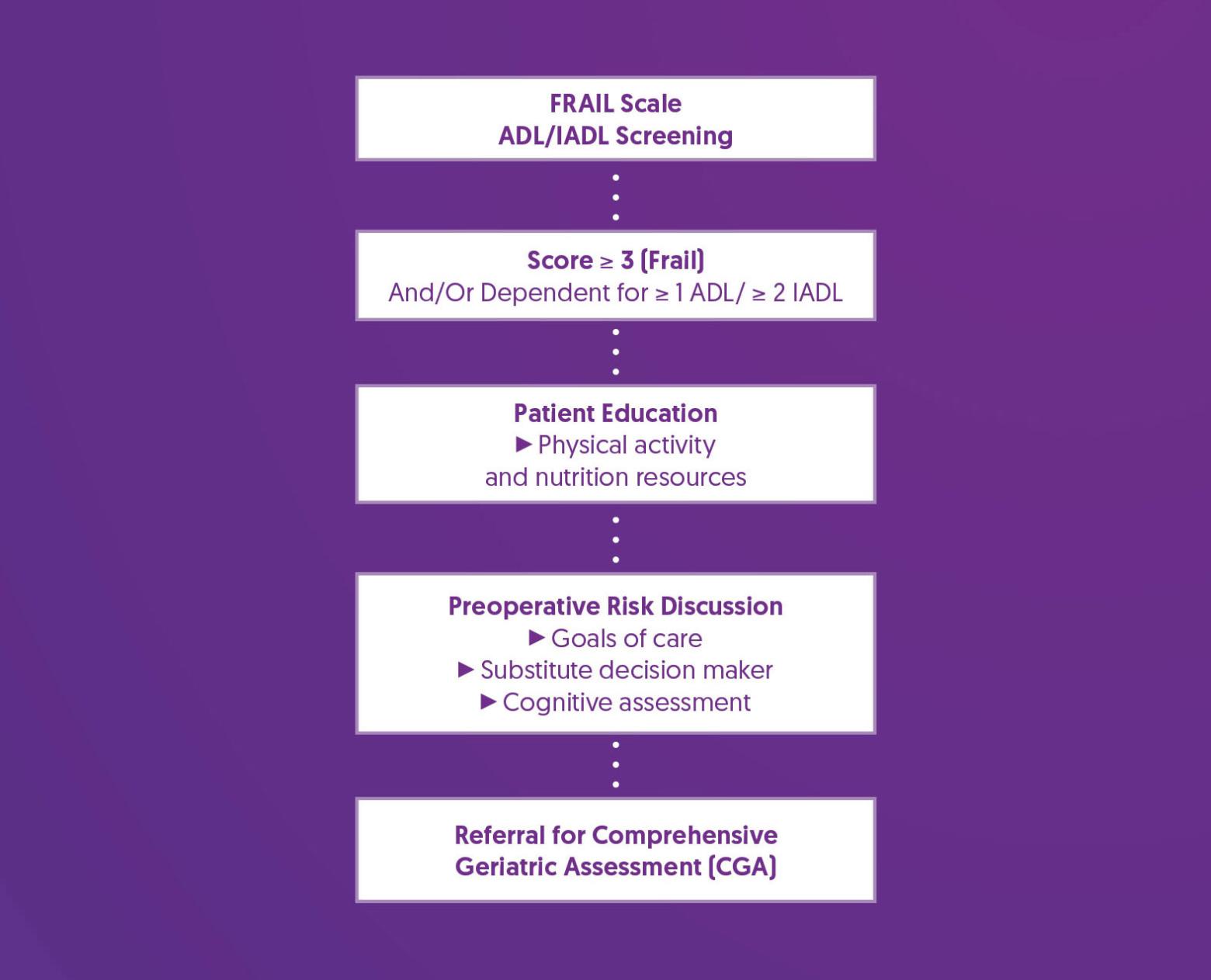

Studies have reported an association between hyperglycemia and adverse infectious and cardiovascular outcomes after cardiac and noncardiac surgery. (1-5) Many studies recommend delaying elective surgery until HbA1c levels are below 8.5, recognizing that this may not be feasible for all patients and that such a cutoff is not currently supported by robust evidence. (6-10)

Screening Tools

Glycemic Control Screening Questions extrapolated from BC Guidelines for Diabetes Care (11). The CANRISK questionnaire is a validated risk tool for patients to self-assess their diabetes risk. (11)

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

|

Patient Education |

|

| Referral for Diabetes Diagnoses and Management (No Pre-Existing Diabetes) |

|

| Referral for Glycemic Optimization (Known Diabetes) |

|

| Consider Delaying for Glycemic Optimization |

|

References

1. Gustafsson, U. O., Thorell, A., Soop, M., Ljungqvist, O., & Nygren, J. (2009). Haemoglobin A1c as a predictor of postoperative hyperglycaemia and complications after major colorectal surgery. The British journal of surgery, 96(11), 1358–1364. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6724

2. Dronge, A. S., Perkal, M. F., Kancir, S., Concato, J., Aslan, M., & Rosenthal, R. A. (2006). Long-term glycemic control and postoperative infectious complications. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960), 141(4), 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.141.4.375

3. Han, H. S., & Kang, S. B. (2013). Relations between long-term glycemic control and postoperative wound and infectious complications after total knee arthroplasty in type 2 diabetics. Clinics in orthopedic surgery, 5(2), 118–123. https://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2013.5.2.118

4. Kwon, S., Thompson, R., Dellinger, P., Yanez, D., Farrohki, E., & Flum, D. (2013). Importance of perioperative glycemic control in general surgery: a report from the Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Annals of surgery, 257(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b6bbc

5. Noordzij, P. G., Boersma, E., Schreiner, F., Kertai, M. D., Feringa, H. H., Dunkelgrun, M., Bax, J. J., Klein, J., & Poldermans, D. (2007). Increased preoperative glucose levels are associated with perioperative mortality in patients undergoing noncardiac, nonvascular surgery. European journal of endocrinology, 156(1), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje.1.02321

6. ElSayed, N. A., Aleppo, G., Aroda, V. R., Bannuru, R. R., Brown, F. M., Bruemmer, D., Collins, B. S., Hilliard, M. E., Isaacs, D., Johnson, E. L., Kahan, S., Khunti, K., Leon, J., Lyons, S. K., Perry, M. L., Prahalad, P., Pratley, R. E., Seley, J. J., Stanton, R. C., Gabbay, R. A., … on behalf of the American Diabetes Association (2023). 16. Diabetes Care in the Hospital: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes care, 46(Suppl 1), S267–S278. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S016

7. Membership of the Working Party, Barker, P., Creasey, P. E., Dhatariya, K., Levy, N., Lipp, A., Nathanson, M. H., Penfold, N., Watson, B., & Woodcock, T. (2015). Peri-operative management of the surgical patient with diabetes 2015: Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Anaesthesia, 70(12), 1427–1440. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.13233

8. Halvorsen, S., Mehilli, J., Cassese, S., Hall, T. S., Abdelhamid, M., Barbato, E., De Hert, S., de Laval, I., Geisler, T., Hinterbuchner, L., Ibanez, B., Lenarczyk, R., Mansmann, U. R., McGreavy, P., Mueller, C., Muneretto, C., Niessner, A., Potpara, T. S., Ristić, A., Sade, L. E., Schirmer, H., Schüpke, S., Sillesen, H., Skulstad, H., Torracca, L., Tutarel, O., Van Der Meer, P., Wojakowski, W., Zacharowski, K., ESC Scientific Document Group. (2022). 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. European heart journal, 43(39), 3826–3924. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac270

9. Rajan, N., Duggan, E. W., Abdelmalak, B. B., Butz, S., Rodriguez, L. V., Vann, M. A., & Joshi, G. P. (2024). Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia Updated Consensus Statement on Perioperative Blood Glucose Management in Adult Patients With Diabetes Mellitus Undergoing Ambulatory Surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia, 139(3), 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006791

10. Giori, N. J., Ellerbe, L. S., Bowe, T., Gupta, S., & Harris, A. H. (2014). Many diabetic total joint arthroplasty candidates are unable to achieve a preoperative hemoglobin A1c goal of 7% or less. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, 96(6), 500–504. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.L.01631

11. Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. (2021). Diabetes Care. British Columbia Medical Services Commission. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/diabetes

12. Diabetes Canada. (n.d.). Individualizing your patient’s A1C target. Retrieved October 27, 2024, from https://guidelines.diabetes.ca/reduce-complications/a1ctarget

Goals of Care

One in three high-risk patients choosing surgery will experience serious medical complications leading to long-term decline in health and quality of life. Often patients do not receive the information they need to make an informed decision about surgery. (1)

Shared decision making is a collaborative process between clinicians and patients, which aims to select the most suitable treatment option based on best available evidence and informed patient preferences. (1)

Screening Tools

- Do you have an advanced care plan - a list of instructions to help guide a trusted person to make health care treatment decisions on your behalf if required?

- Have you identified a substitute decision maker - someone you trust to make health care treatment decisions on your behalf if you are unable to do it yourself?

- Is the patient at higher risk of perioperative complications? (e.g., advanced age, frailty, poor functional capacity, moderate/highly invasive surgery, multiple comorbidities)

Optimization is recommended for patients that answer No to question 1 or 2, or Yes to question 3.

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Preoperative Goals of Care Discussion |

|

| Referral for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) |

|

References

1. Centre for Perioperative Care. (n.d.). Shared decision making for clinicians. Retrieved October 21, 2024, from https://www.cpoc.org.uk/guidelines-resources-resources/shared-decision-making-clinicians

2. Kruser, J. M., Nabozny, M. J., Steffens, N. M., Brasel, K. J., Campbell, T. C., Gaines, M. E., & Schwarze, M. L. (2015). "Best Case/Worst Case": Qualitative Evaluation of a Novel Communication Tool for Difficult in-the-Moment Surgical Decisions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(9), 1805–1811. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13615

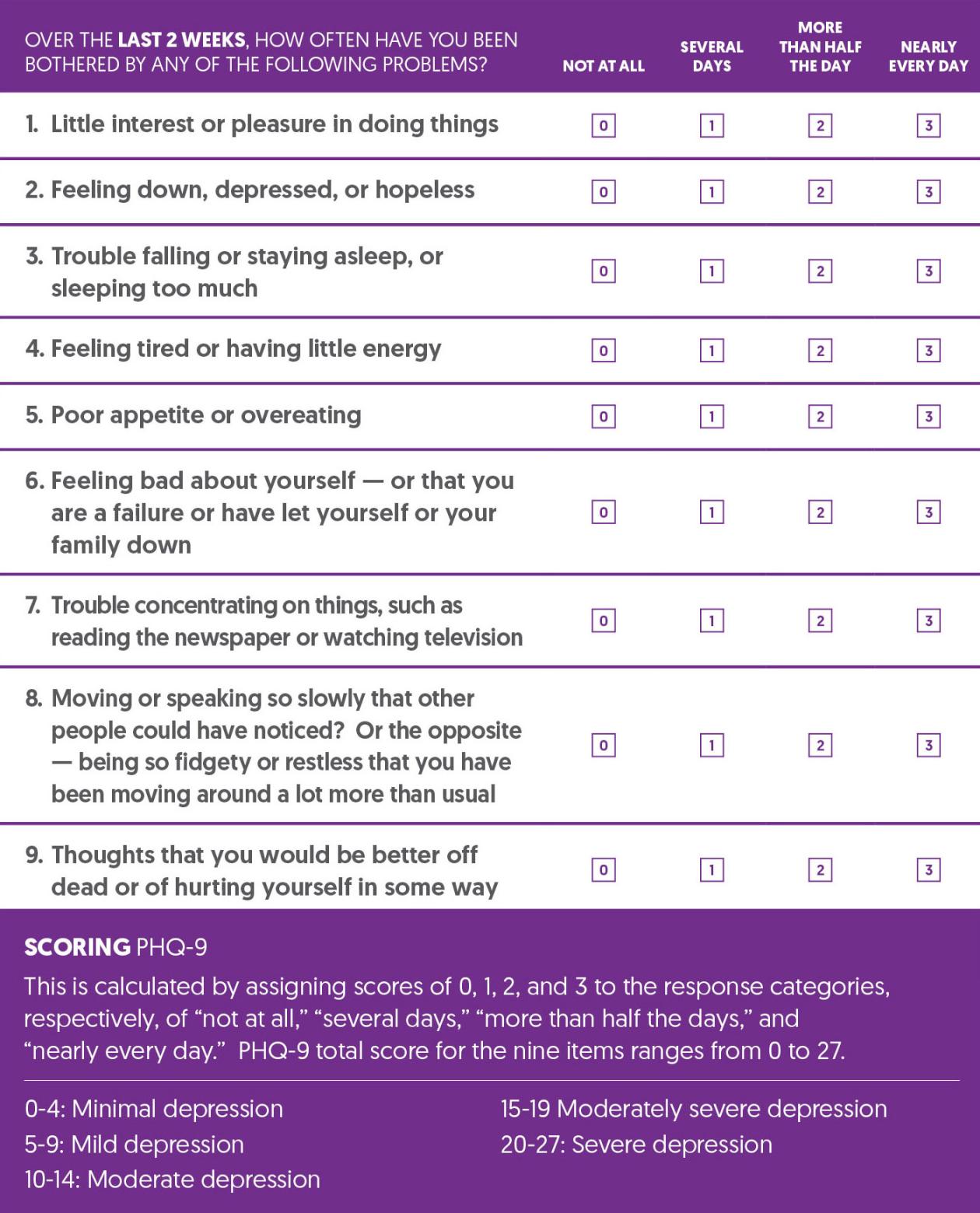

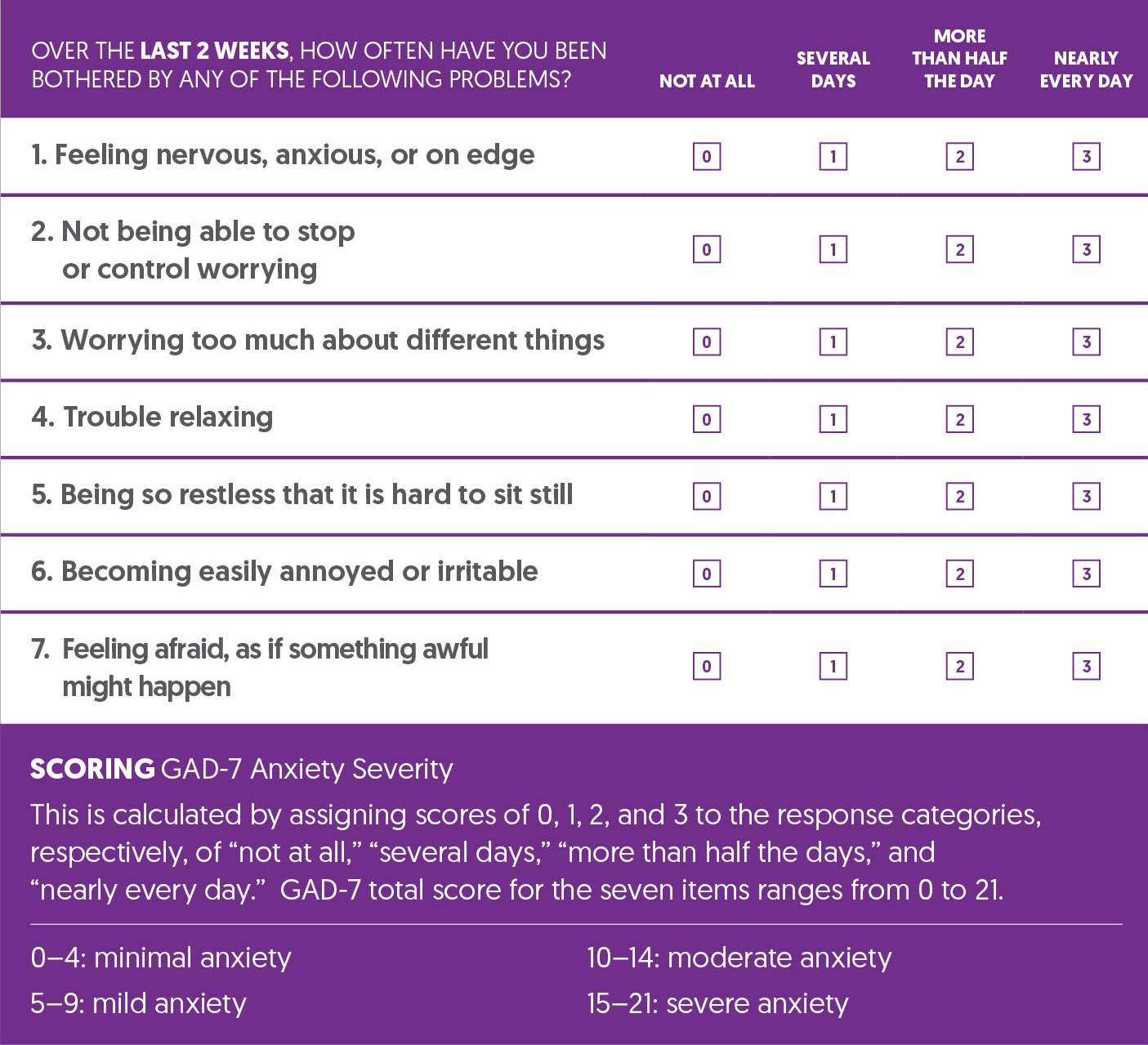

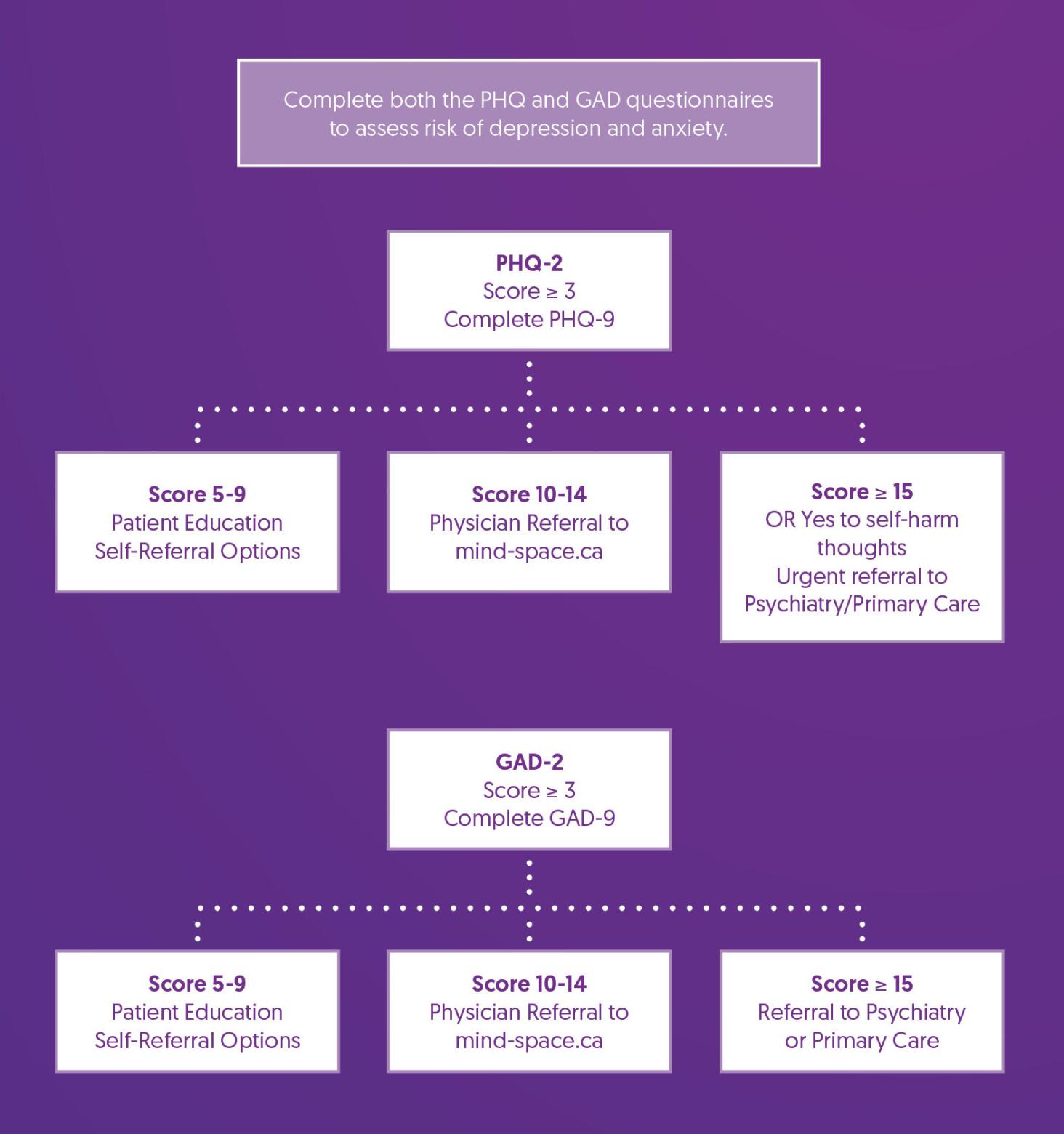

Mental Wellbeing

Significant anxiety and depression are associated with increased postoperative pain, prolonged hospital length of stay, and hospital readmission, as well as many other postoperative complications (1,2). Preoperative education and expectation setting can help reduce postoperative anxiety, depression, and length of stay, and improve patient experiences and outcomes. (3,4)

Screening Tools

The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) is an initial screening tool for depression, comprising the first two questions of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). A PHQ-2 score of 3 or more warrants completion of the PHQ-9. (5,6)

The General Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) is an initial screening tool for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), comprising the first two questions of the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). A GAD-2 score of 3 or more warrants completion of the GAD-7 scale. (7)

While no scale is diagnostic, these tools are intended to help identify pre-surgical patients who may be experiencing more significant symptoms, who may benefit from targeted pre-surgical intervention.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Questionnaire

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Self-Referral Options |

|

| Physician-Referral Options |

|

References

1. Browne, J. A., Sandberg, B. F., D'Apuzzo, M. R., & Novicoff, W. M. (2014). Depression is associated with early postoperative outcomes following total joint arthroplasty: a nationwide database study. The Journal of arthroplasty, 29(3), 481–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.08.025

2. Geoffrion, R., Koenig, N. A., Zheng, M., Sinclair, N., Brotto, L. A., Lee, T., & Larouche, M. (2021). Preoperative depression and anxiety impact on inpatient surgery outcomes: A prospective cohort study. Annals of Surgery Open, 1(e049). https://doi.org/10.1097/AS9.0000000000000049

3. 10. Li, L., Li, S., Sun, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, X., & Qu, H. (2021). Personalized Preoperative Education Reduces Perioperative Anxiety in Old Men with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Gerontology, 67(2), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1159/000511913

4. Ng, S. X., Wang, W., Shen, Q., Toh, Z. A., & He, H. G. (2022). The effectiveness of preoperative education interventions on improving perioperative outcomes of adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of cardiovascular nursing, 21(6), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvab123

5. Instructions for Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) and GAD-7 Measures. (n.d.). Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.phqscreeners.com/images/sites/g/files/g10016261/f/201412/instructions.pdf

6. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

7. Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

Nutrition

Malnutrition is present in approximately 45% of patients at time of admission to hospital. It is often underrecognized and is associated with increased postoperative complications and in-hospital and 30-day mortality. Nutrition risk is also associated with increased length of stay, readmission, and hospital costs. (1-5) Preoperative & early postoperative nutritional intervention are associated with improvements in postoperative complications and mortality. (6)

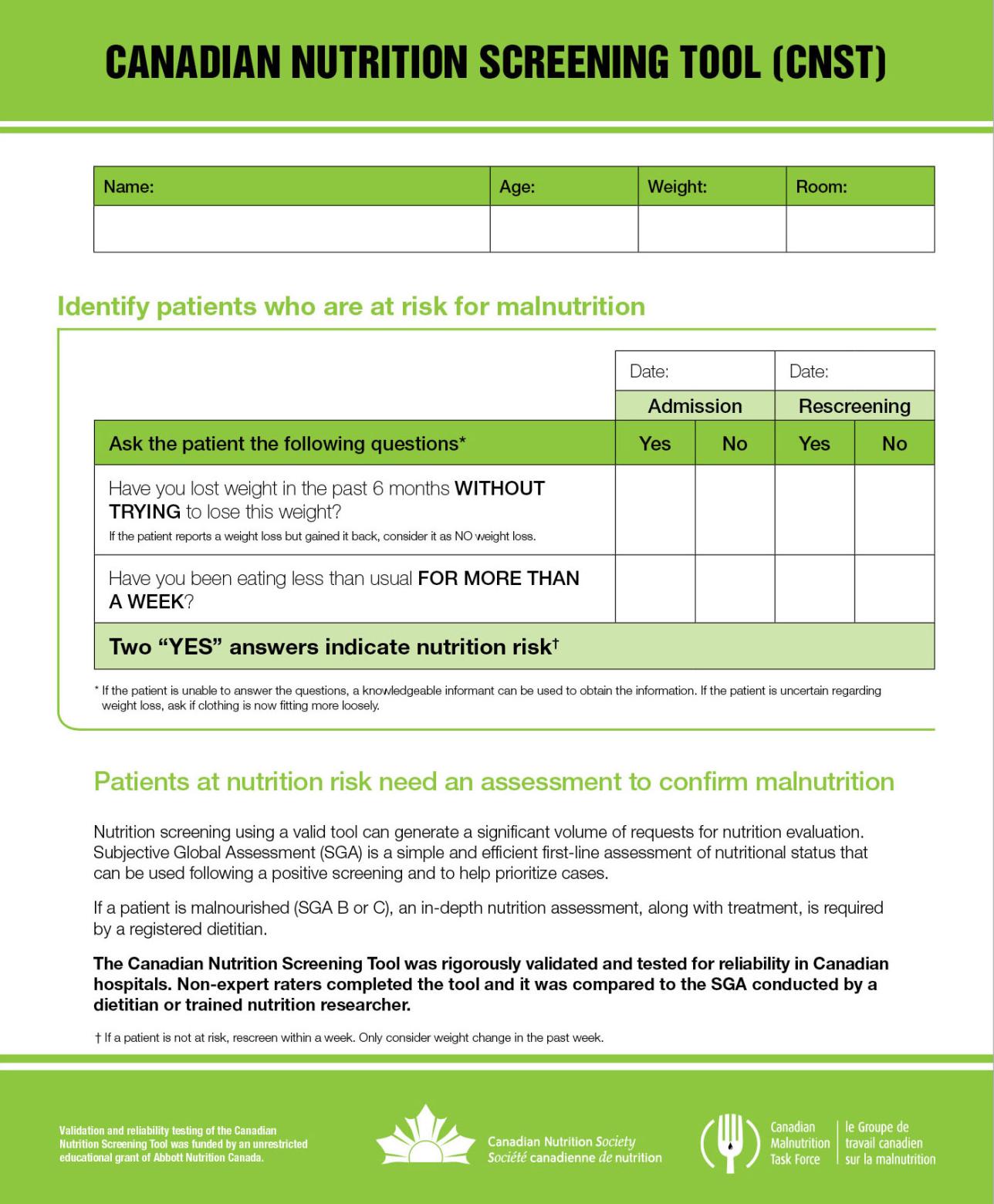

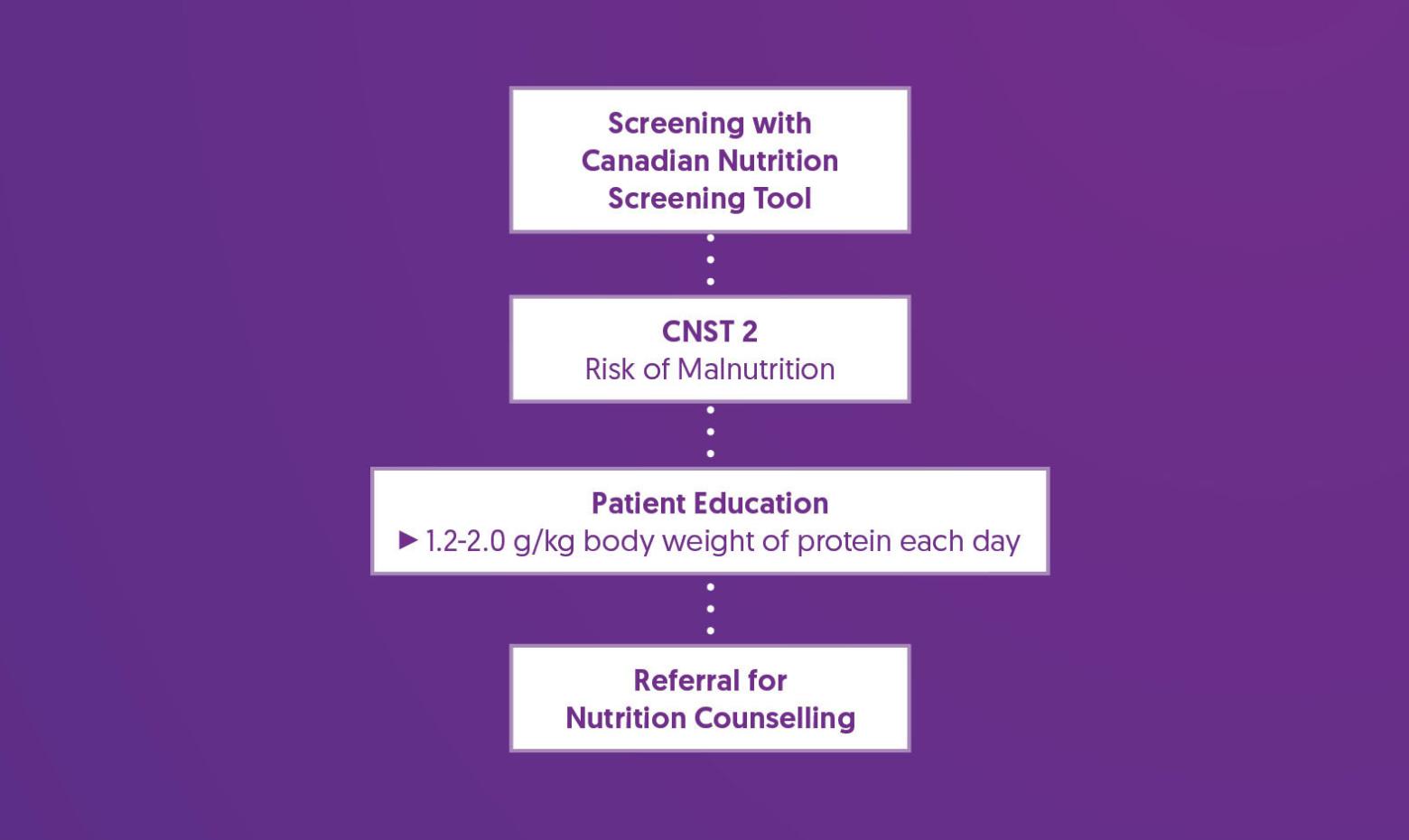

Screening Tools

The Canadian Nutrition Screening Tool (CNST) is a valid and reliable screening tool to identify those patients at risk of malnutrition in the adult acute care environment. (1)

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Referral for Nutrition Counseling |

|

References

1. Laporte, M., Keller, H. H., Payette, H., Allard, J. P., Duerksen, D. R., Bernier, P., Jeejeebhoy, K., Gramlich, L., Davidson, B., Vesnaver, E., & Teterina, A. (2015). Validity and reliability of the new Canadian Nutrition Screening Tool in the 'real-world' hospital setting. European journal of clinical nutrition, 69(5), 558–564. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.270

2. Wong, H. M. K., Qi, D., Ma, B. H. M., Hou, P. Y., Kwong, C. K. W., Lee, A., & Prehab Study Group (2024). Multidisciplinary prehabilitation to improve frailty and functional capacity in high-risk elective surgical patients: a retrospective pilot study. Perioperative medicine (London, England), 13(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-024-00359-x

3. Duerksen, D. R., Keller, H. H., Vesnaver, E., Laporte, M., Jeejeebhoy, K., Payette, H., Gramlich, L., Bernier, P., & Allard, J. P. (2016). Nurses' Perceptions Regarding the Prevalence, Detection, and Causes of Malnutrition in Canadian Hospitals: Results of a Canadian Malnutrition Task Force Survey. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition, 40(1), 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607114548227

4. Duerksen, D. R., Keller, H. H., Vesnaver, E., Allard, J. P., Bernier, P., Gramlich, L., Payette, H., Laporte, M., & Jeejeebhoy, K. (2015). Physicians' perceptions regarding the detection and management of malnutrition in Canadian hospitals: results of a Canadian Malnutrition Task Force survey. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition, 39(4), 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607114534731

5. Allard, J. P., Keller, H., Jeejeebhoy, K. N., Laporte, M., Duerksen, D. R., Gramlich, L., Payette, H., Bernier, P., Vesnaver, E., Davidson, B., Teterina, A., & Lou, W. (2016). Malnutrition at Hospital Admission-Contributors and Effect on Length of Stay: A Prospective Cohort Study From the Canadian Malnutrition Task Force. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition, 40(4), 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607114567902

6. Martínez-Ortega, A. J., Piñar-Gutiérrez, A., Serrano-Aguayo, P., González-Navarro, I., Remón-Ruíz, P. J., Pereira-Cunill, J. L., & García-Luna, P. P. (2022). Perioperative Nutritional Support: A Review of Current Literature. Nutrients, 14(8), 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081601

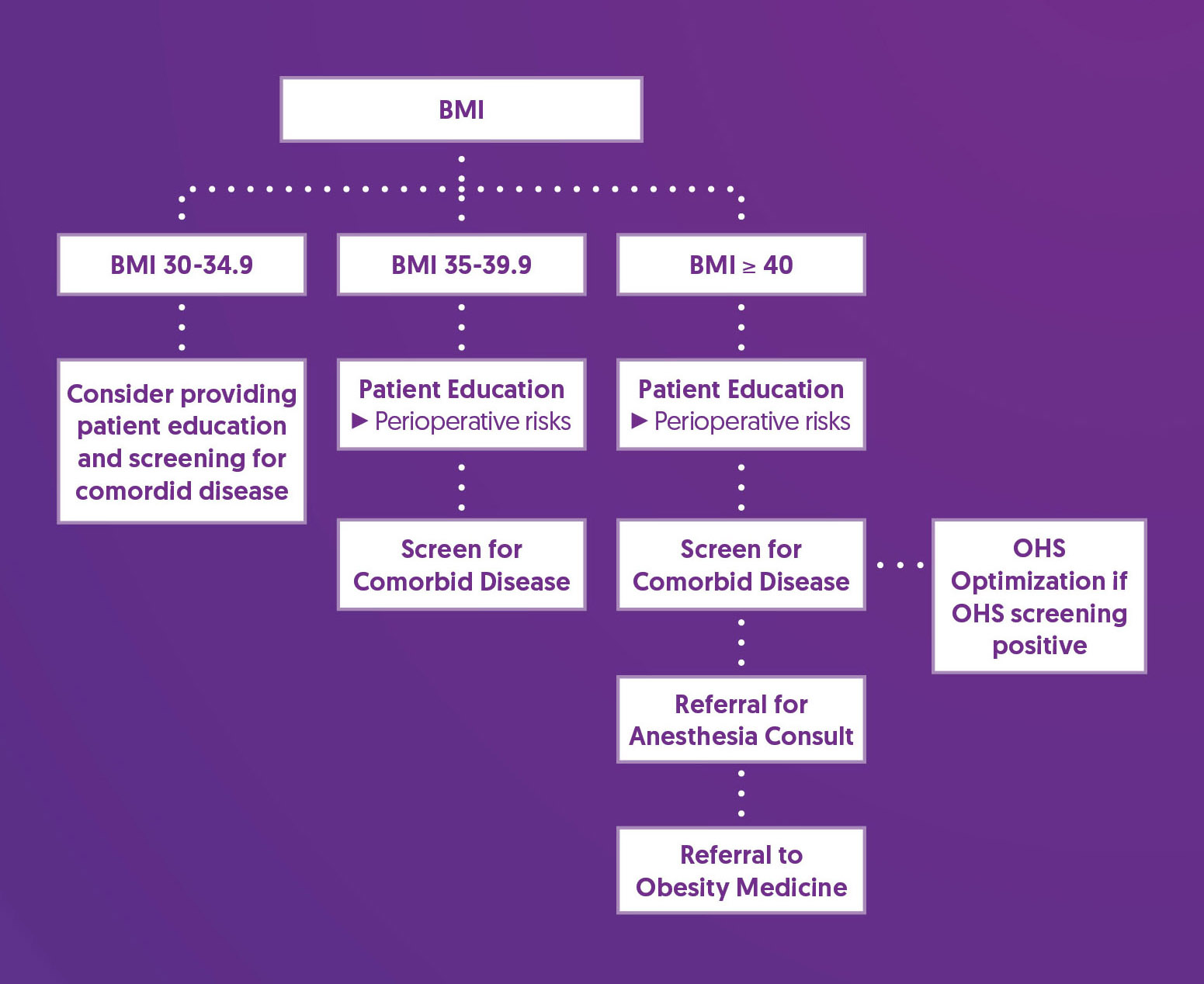

Obesity

Obesity is linked to several conditions, such as type II diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea, that may increase perioperative risks. Comorbidities may outweigh BMI in assessing these risks. (1-4)

For patients with class 1* obesity (BMI: 30–34.9), perioperative risks are mainly limited to venous thromboembolism. In class 2* obesity (BMI: 35–39.9) and higher, there is a modest increase in risks, including postoperative pulmonary complications, wound infections, longer hospital stays, increased blood loss, longer surgeries, and renal failure. (5-8)

Although high BMI is associated with higher perioperative risks, there is limited research on the effects of preoperative weight loss through diet and limited evidence to suggest delaying surgery based on BMI. (9)

*Classification is based on Caucasian populations. Lower cutoffs have been recommended for other ethnicities. (10)

Screening Tools

Although BMI is easy to obtain and therefore used to identify and categorize severity of obesity, integrating other indices (e.g., waist to hip ratio, waist circumference, and percent body fat) may improve predictions of metabolic health, comorbid conditions, and perioperative risk stratification. (1-3)

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Screen for Comorbid Disease |

|

| Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome (OHS) |

|

| Referral for Anesthesia Consult |

|

| Consider Referral to Obesity Medicine |

|

References

1. Wharton, S., Lau, D. C. W., Vallis, M., Sharma, A. M., Biertho, L., Campbell-Scherer, D., Adamo, K., Alberga, A., Bell, R., Boulé, N., Boyling, E., Brown, J., Calam, B., Clarke, C., Crowshoe, L., Divalentino, D., Forhan, M., Freedhoff, Y., Gagner, M., Glazer, S., … Wicklum, S. (2020). Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 192(31), E875–E891. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.191707

2. Gurunathan, U., & Myles, P. S. (2016). Limitations of body mass index as an obesity measure of perioperative risk. British journal of anaesthesia, 116(3), 319–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aev541

3. Ledford, C. K., Ruberte Thiele, R. A., Appleton, J. S., Jr, Butler, R. J., Wellman, S. S., Attarian, D. E., Queen, R. M., & Bolognesi, M. P. (2014). Percent body fat more associated with perioperative risks after total joint arthroplasty than body mass index. The Journal of arthroplasty, 29(9 Suppl), 150–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.12.036

4. Chan, W. K., Chuah, K. H., Rajaram, R. B., Lim, L. L., Ratnasingam, J., & Vethakkan, S. R. (2023). Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of obesity & metabolic syndrome, 32(3), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes23052

5. Dindo, D., Muller, M. K., Weber, M., & Clavien, P. A. (2003). Obesity in general elective surgery. Lancet (London, England), 361(9374), 2032–2035. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13640-9

6. De Oliveira, G. S., Jr, McCarthy, R. J., Davignon, K., Chen, H., Panaro, H., & Cioffi, W. G. (2017). Predictors of 30-Day Pulmonary Complications after Outpatient Surgery: Relative Importance of Body Mass Index Weight Classifications in Risk Assessment. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 225(2), 312–323.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.04.013

7. Madsen, H. J., Gillette, R. A., Colborn, K. L., Henderson, W. G., Dyas, A. R., Bronsert, M. R., Lambert-Kerzner, A., & Meguid, R. A. (2023). The association between obesity and postoperative outcomes in a broad surgical population: A 7-year American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement analysis. Surgery, 173(5), 1213–1219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2023.02.001

8. Kassahun, W. T., Mehdorn, M., & Babel, J. (2022). The impact of obesity on surgical outcomes in patients undergoing emergency laparotomy for high-risk abdominal emergencies. BMC surgery, 22(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-022-01466-6

9. Pavlovic, N., Boland, R. A., Brady, B., Genel, F., Harris, I. A., Flood, V. M., & Naylor, J. M. (2021). Effect of weight-loss diets prior to elective surgery on postoperative outcomes in obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical obesity, 11(6), e12485. https://doi.org/10.1111/cob.12485

10. Li, Z., Daniel, S., Fujioka, K., & Umashanker, D. (2023). Obesity among Asian American people in the United States: A review. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 31(2), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23639

11. Chau, E. H., Lam, D., Wong, J., Mokhlesi, B., & Chung, F. (2012). Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a review of epidemiology, pathophysiology, and perioperative considerations. Anesthesiology, 117(1), 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825add60

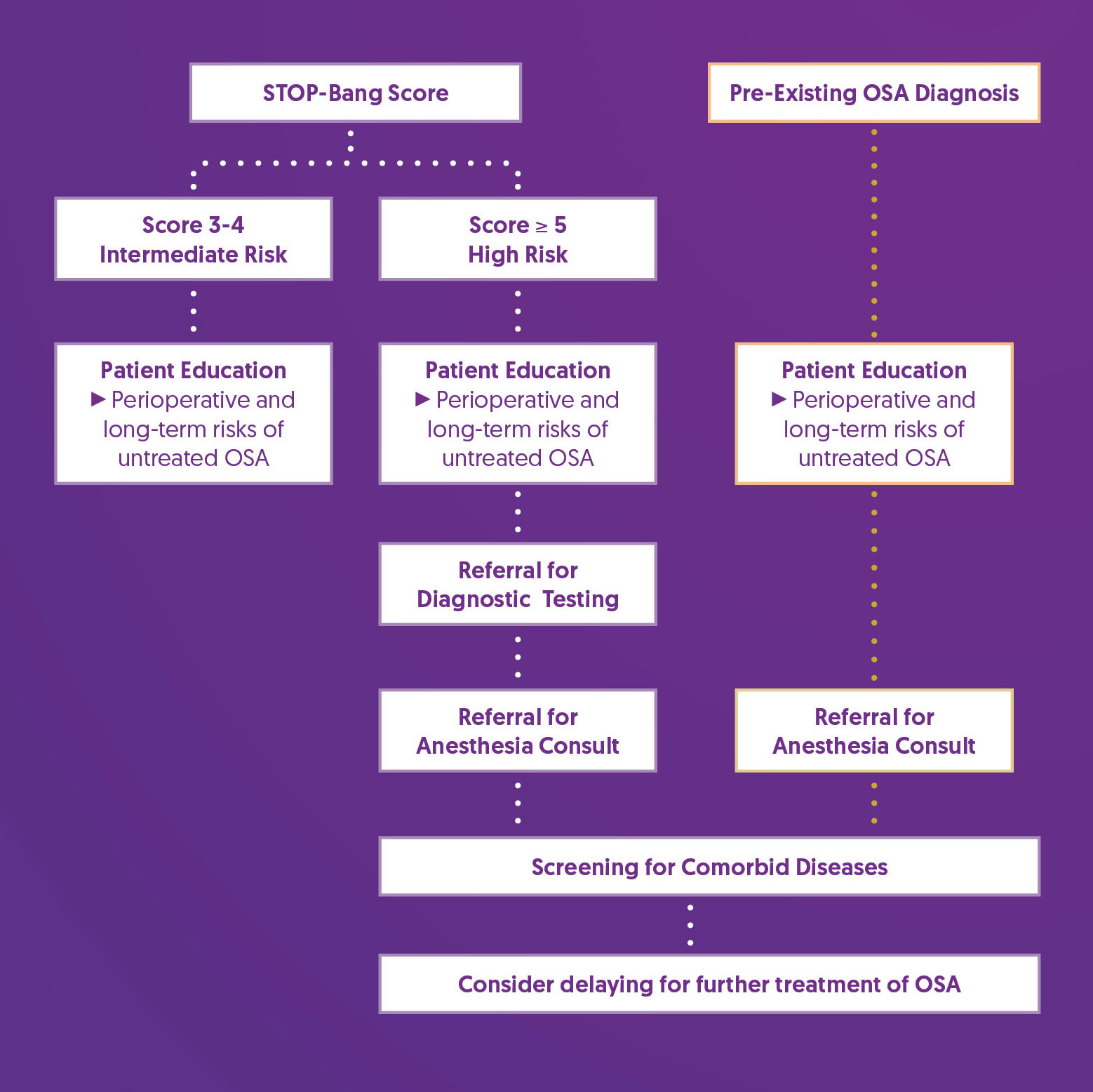

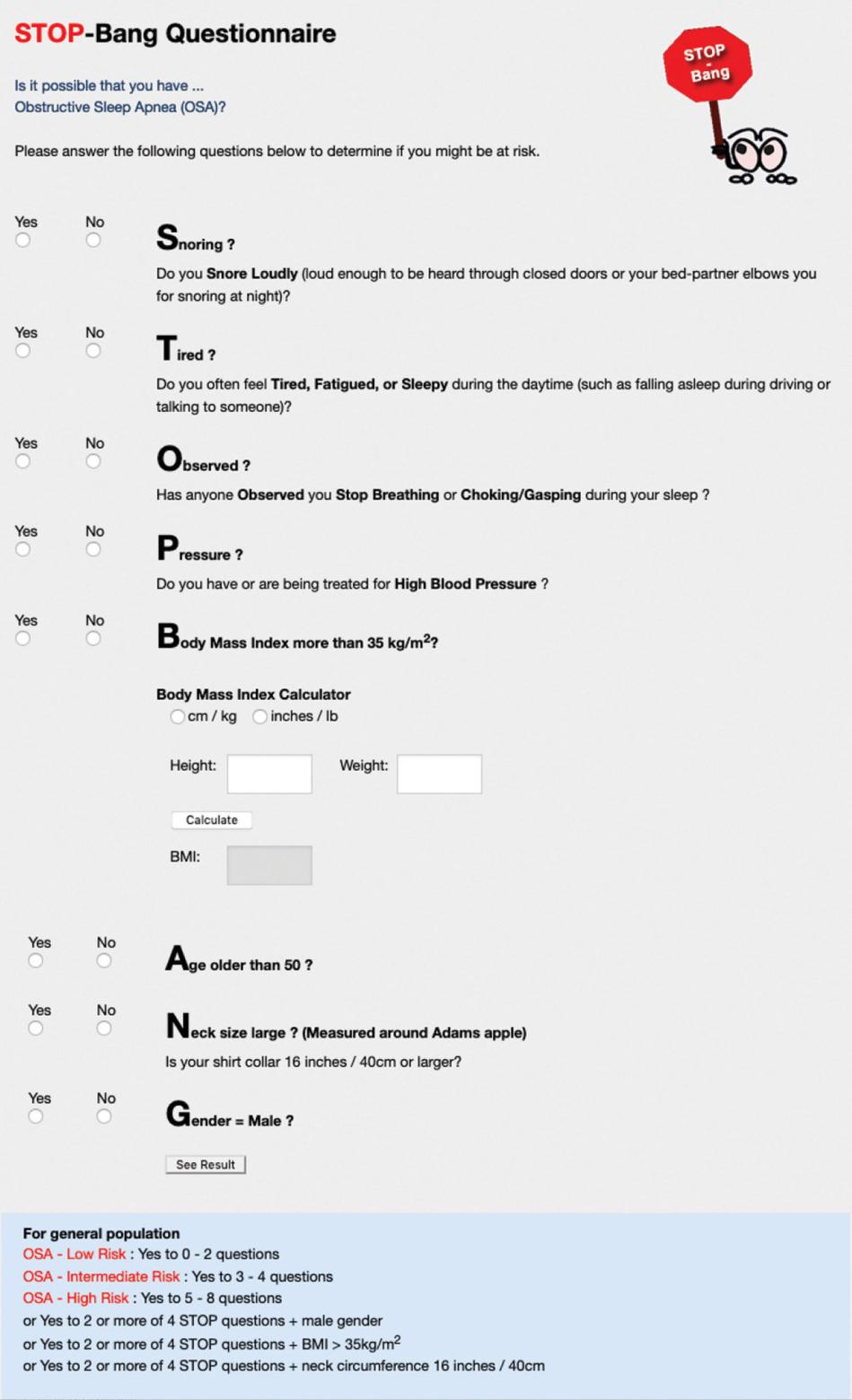

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a chronic medical condition that is commonly undiagnosed. The most common form of sleep-disordered breathing, it is characterized by recurring transient obstructions of airflow that occur exclusively during sleep. OSA is associated with increased risk of perioperative complications, including postoperative respiratory failure, cardiac events, and ICU transfer, and should be identified and treated as early as possible to help reduce this risk. (1-7)

Screening Tools

The STOP-Bang questionnaire is a validated tool for preoperative screening for OSA, assessing the likelihood of moderate to severe OSA. Scores of 5 or higher indicate a high probability of moderate to severe OSA. (8)

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Referral for Diagnostic Testing |

|

| Referral for Anesthesia Consult |

|

| Screening for Comorbid Disease |

|

| Consider delaying for further treatment of OSA |

|

References

1. Roesslein, M., & Chung, F. (2018). Obstructive sleep apnoea in adults: peri-operative considerations: A narrative review. European journal of anaesthesiology, 35(4), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000000765

2. Mutter, T. C., Chateau, D., Moffatt, M., Ramsey, C., Roos, L. L., & Kryger, M. (2014). A matched cohort study of postoperative outcomes in obstructive sleep apnea: could preoperative diagnosis and treatment prevent complications? Anesthesiology, 121(4), 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000407

3. Abdelsattar, Z. M., Hendren, S., Wong, S. L., Campbell, D. A., Jr, & Ramachandran, S. K. (2015). The Impact of Untreated Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Cardiopulmonary Complications in General and Vascular Surgery: A Cohort Study. Sleep, 38(8), 1205–1210. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4892

4. Patel, D., Tsang, J., Saripella, A., Nagappa, M., Islam, S., Englesakis, M., & Chung, F. (2022). Validation of the STOP questionnaire as a screening tool for OSA among different populations: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 18(5), 1441–1453. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.9820

5. Melesse, D. Y., Mekonnen, Z. A., Kassahun, H. G., & Chekol, W. B. (2020). Evidence based perioperative optimization of patients with obstructive sleep apnea in Resource Limited Areas: A systematic review. International Journal of Surgery Open, 23, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijso.2020.02.002

6. Cozowicz, C., & Memtsoudis, S. G. (2021). Perioperative Management of the Patient With Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Narrative Review. Anesthesia and analgesia, 132(5), 1231–1243. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005444

7. Chaudhry, R. A., Zarmer, L., West, K., & Chung, F. (2024). Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Risk of Postoperative Complications after Non-Cardiac Surgery. Journal of clinical medicine, 13(9), 2538. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13092538

8. Hwang, M., Nagappa, M., Guluzade, N., Saripella, A., Englesakis, M., & Chung, F. (2022). Validation of the STOP-Bang questionnaire as a preoperative screening tool for obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC anesthesiology, 22(1), 366. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-022-01912-1

9. Chung, F., Memtsoudis, S. G., Ramachandran, S. K., Nagappa, M., Opperer, M., Cozowicz, C., Patrawala, S., Lam, D., Kumar, A., Joshi, G. P., Fleetham, J., Ayas, N., Collop, N., Doufas, A. G., Eikermann, M., Englesakis, M., Gali, B., Gay, P., Hernandez, A. V., Kaw, R., … Auckley, D. (2016). Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Guidelines on Preoperative Screening and Assessment of Adult Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesia and analgesia, 123(2), 452–473. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001416

Pain Management

Significant acute postoperative pain is common, even among those on an established pain management protocol (1). Pain after surgery is associated with increased risk of postoperative readmission to hospital, emergency department visits, myocardial injury, delirium, and chronic pain (2-7). Postoperative pain control may be improved by addressing modifiable patient risk factors such as sleep, BMI, depression, anxiety, and preoperative pain (8).

Screening Tools

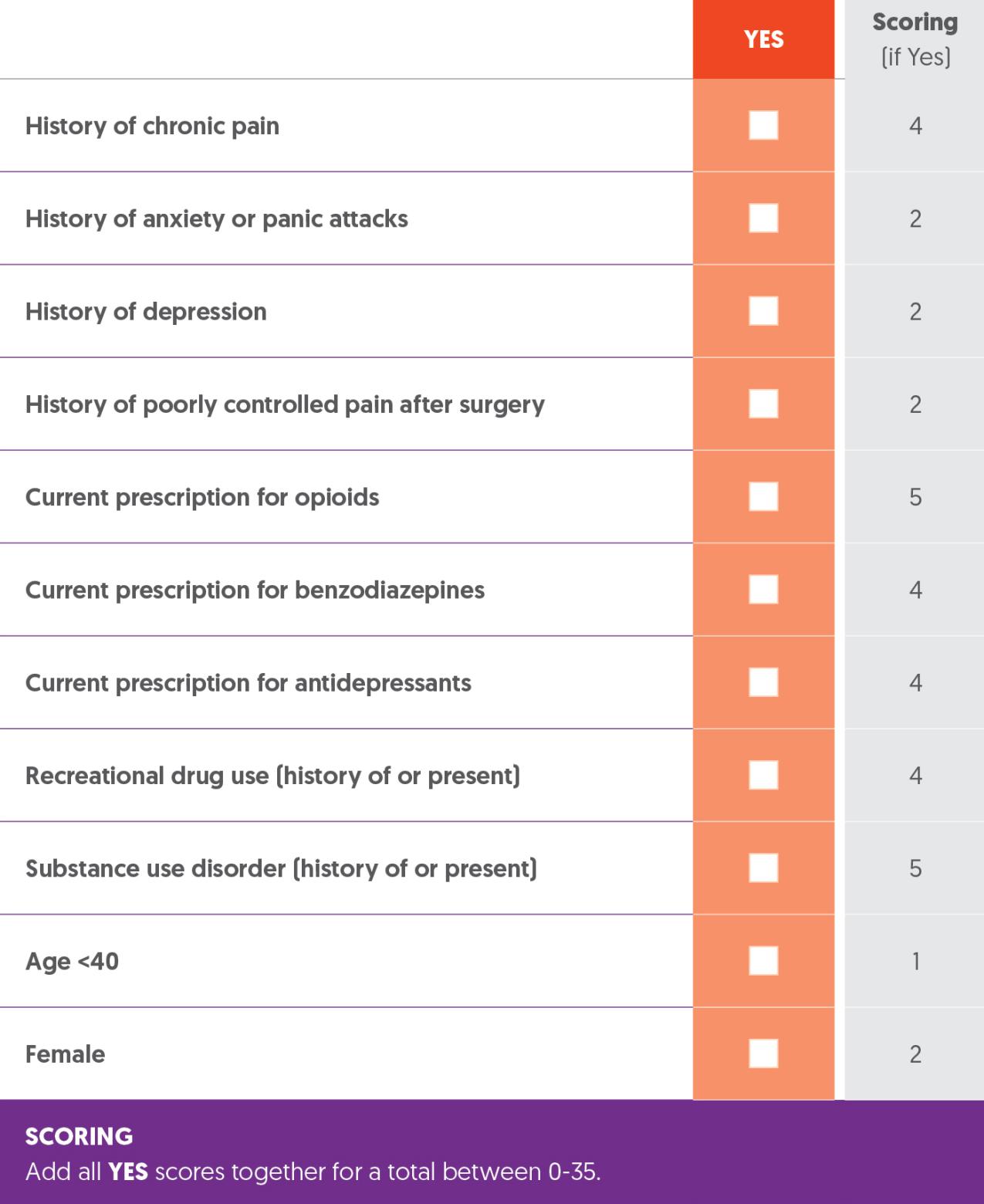

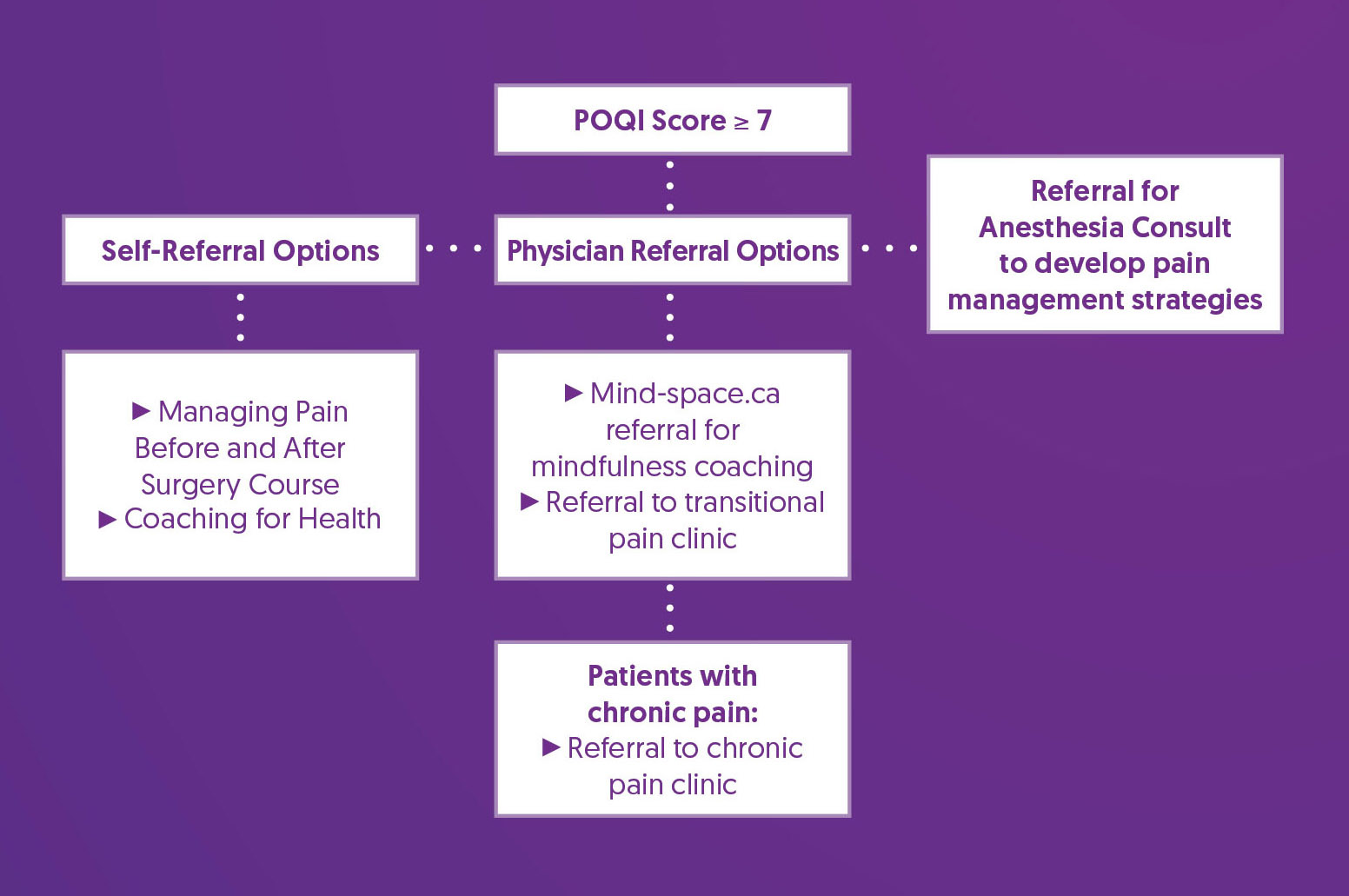

The Perioperative Opioid Quality Improvement (POQI) score is an algorithm being developed at St. Paul's Hospital. It aims to identify patients at increased risk of significant postoperative pain and long-term opioid use, so that their care plans may be tailored with the intent of helping reduce initial opioid consumption. (9) It incorporates several variables associated with increased risk for developing postoperative pain and uses consumption of > 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day while inpatient after surgery as a surrogate marker for assessing performance (9). While the POQI score is not validated, it was selected to support postoperative pain risk stratification based on local BC experience with the tool. A POQI score >= 7 is considered to be ‘increased risk.’

Perioperative Opioid Quality Improvement (POQI) Assessment

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Self-Referral Options |

|

| Referral for Anesthesia Consult |

|

| Physician-Referral Options |

|

References

1. Sommer, M., de Rijke, J. M., van Kleef, M., Kessels, A. G., Peters, M. L., Geurts, J. W., Gramke, H. F., & Marcus, M. A. (2008). The prevalence of postoperative pain in a sample of 1490 surgical inpatients. European journal of anaesthesiology, 25(4), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265021507003031

2. Katz, J., Jackson, M., Kavanagh, B. P., & Sandler, A. N. (1996). Acute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy pain. The Clinical journal of pain, 12(1), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-199603000-00009

3. Hernandez-Boussard, T., Graham, L. A., Desai, K., Wahl, T. S., Aucoin, E., Richman, J. S., Morris, M. S., Itani, K. M., Telford, G. L., & Hawn, M. T. (2017). The fifth vital sign: Postoperative pain predicts 30-day readmissions and subsequent emergency department visits. Annals of Surgery, 266(3), 516–524. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002372

4. Dubljanin Raspopović, E., Meissner, W., Zaslansky, R., Kadija, M., Tomanović Vujadinović, S., & Tulić, G. (2021). Associations between early postoperative pain outcome measures and late functional outcomes in patients after knee arthroplasty. PLOS ONE, 16(7), e0253147. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253147

5. Buvanendran, A., Della Valle, C. J., Kroin, J. S., Shah, M., Moric, M., Tuman, K. J., & McCarthy, R. J. (2019). Acute postoperative pain is an independent predictor of chronic postsurgical pain following total knee arthroplasty at 6 months: A prospective cohort study. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine, 44(3), e100036. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2018-100036

6. Turan, A., Leung, S., Bajracharya, G. R., Babazade, R., Barnes, T., Schacham, Y. N., Mao, G., Zimmerman, N., Ruetzler, K., Maheshwari, K., Esa, W. A. S., & Sessler, D. I. (2020). Acute Postoperative Pain Is Associated With Myocardial Injury After Noncardiac Surgery. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 131(3), 822–829. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005033

7. Khaled, M., Sabac, D., Fuda, M., Koubaesh, C., Gallab, J., Qu, M., Lo Bianco, G., Shanthanna, H., Paul, J., Thabane, L., & Marcucci, M. (2024). Postoperative pain and neurocognitive outcomes after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. British journal of anaesthesia, S0007-0912(24)00550-6. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.08.032

8. Yang, M. M. H., Hartley, R. L., Leung, A. A., Ronksley, P. E., Jetté, N., Casha, S., & Riva-Cambrin, J. (2019). Preoperative predictors of poor acute postoperative pain control: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open,9(4), e025091. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025091

9. Görges, M., Sujan, J., West, N. C., Sreepada, R. S., Wood, M. D., Payne, B. A., Shetty, S., Gelinas, J. P., & Sutherland, A. M. (2024). Postsurgical Pain Risk Stratification to Enhance Pain Management Workflow in Adult Patients: Design, Implementation, and Pilot Evaluation. JMIR perioperative medicine, 7, e54926. https://doi.org/10.2196/54926

Physical Activity

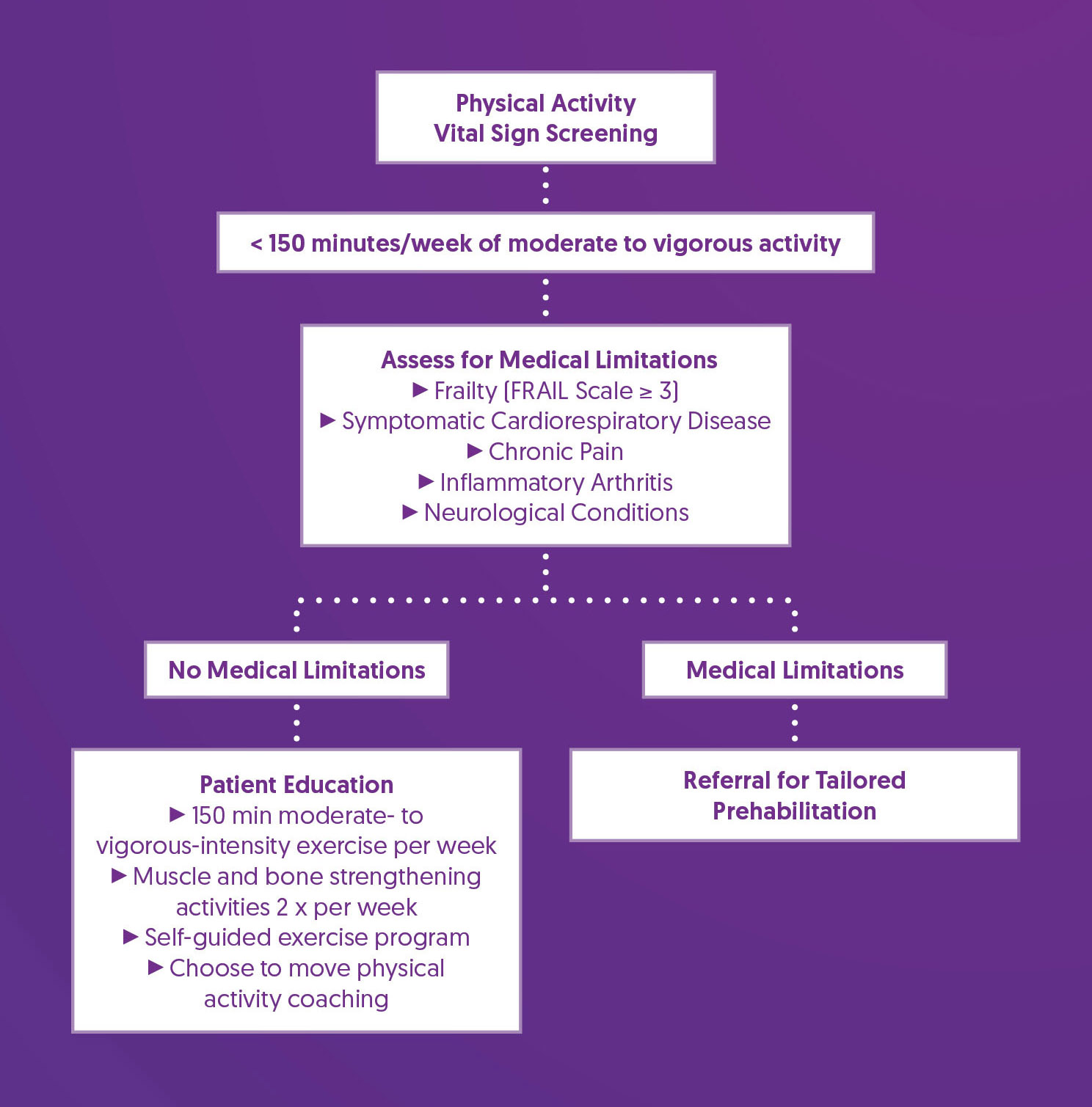

Poor functional capacity and physical fitness are associated with poor surgical outcomes including prolonged hospital length of stay and increased risk of postoperative complications. Increasing physical fitness can improve resilience and recovery after surgery. (1,2)

Screening Tools

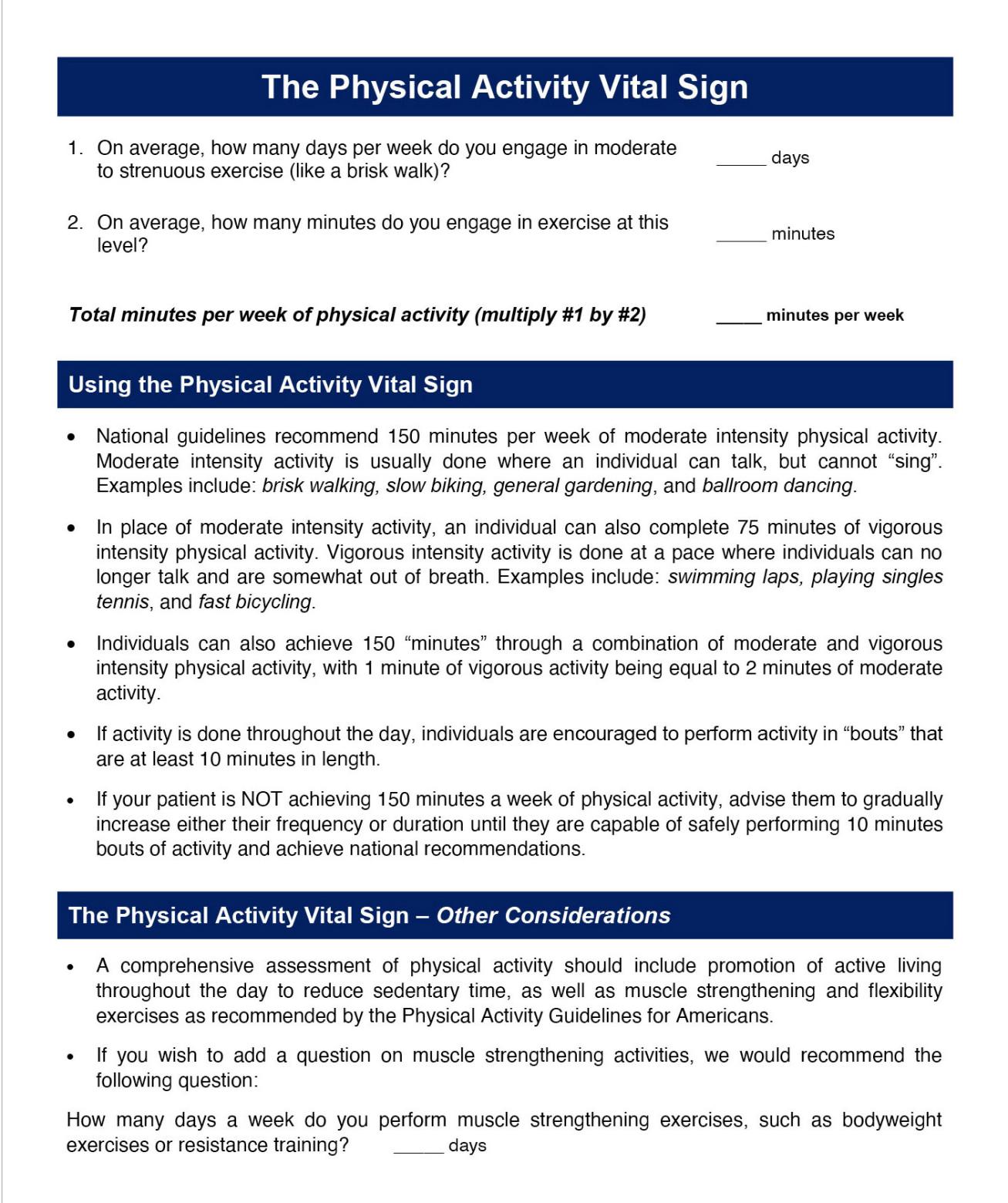

The Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) Calculator is a quick and easy way to flag sedentary patients for referral and counseling.

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Referral for Tailored Prehabilitation |

|

References

1. Barberan-Garcia, A., Ubré, M., Roca, J., Lacy, A. M., Burgos, F., Risco, R., Momblán, D., Balust, J., Blanco, I., & Martínez-Pallí, G. (2018). Personalised Prehabilitation in High-risk Patients Undergoing Elective Major Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized Blinded Controlled Trial. Annals of surgery, 267(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002293

2. Gillis, C., Ljungqvist, O., & Carli, F. (2022). Prehabilitation, enhanced recovery after surgery, or both? A narrative review. British journal of anaesthesia, 128(3), 434–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.12.007

Smoking Cessation

Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for perioperative pulmonary, cardiovascular, bleeding and wound healing complications. (1,2) There is some evidence that vaping (or the use of e-cigarettes) is also associated with these complications. (3) The likelihood that quit-motivated patients can abstain from smoking is increased by use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). (4)

Screening Tools

Screening Questions:

- Do you currently use products that contain tobacco or nicotine? (e.g., smoking cigarettes or e-cigarettes, vaping nicotine, or chewing tobacco)

- If Yes, what type of tobacco/nicotine product?

- If cigarettes, how many packs/day? If other, how much & how often?

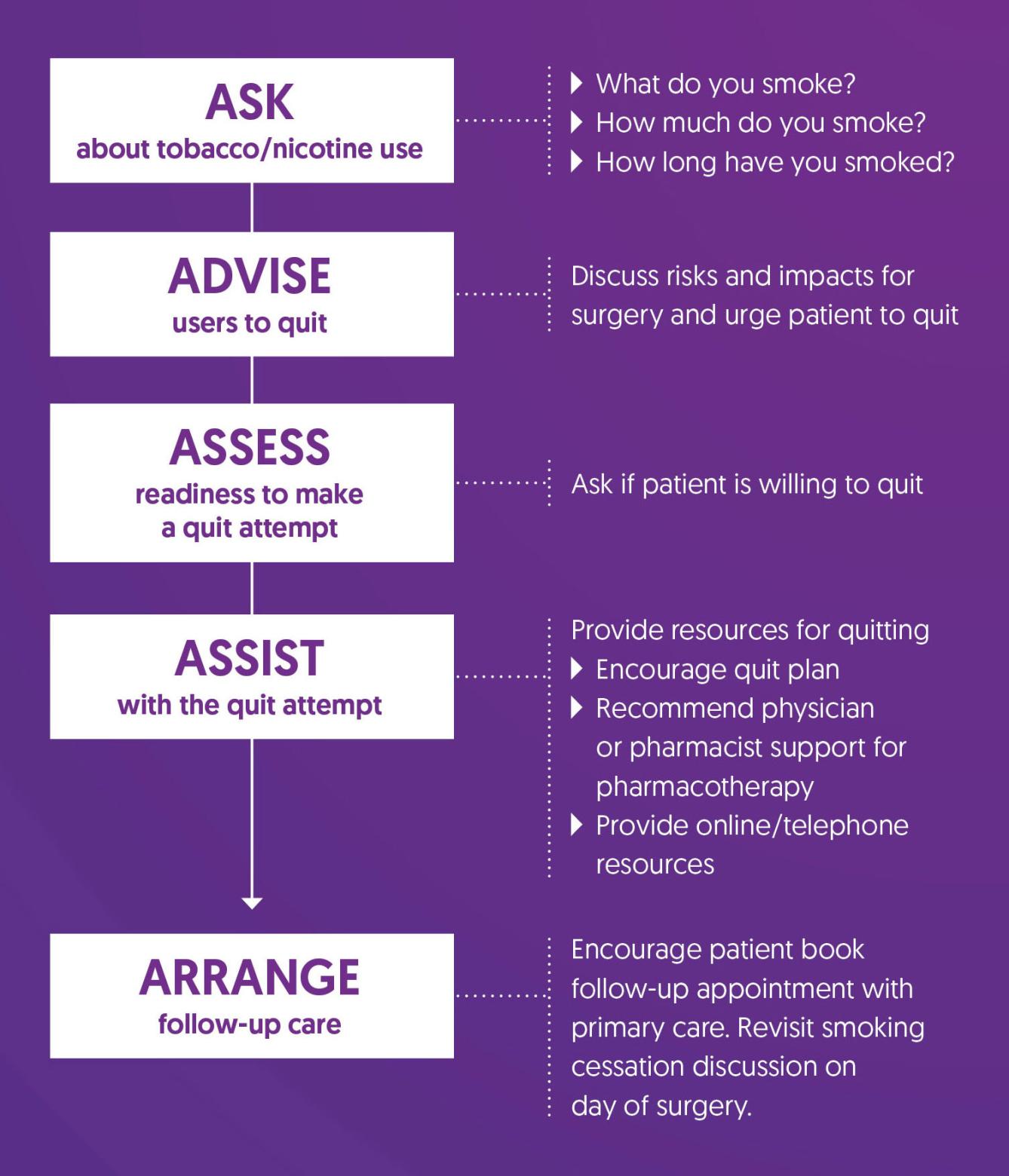

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

5 A’s Algorithm for Smoking Cessation (5).

|

| Referral for Follow-up |

|

References

1. Eliasen, M., Grønkjær, M., Skov-Ettrup, L. S., Mikkelsen, S. S., Becker, U., Tolstrup, J. S., & Flensborg-Madsen, T. (2013). Preoperative alcohol consumption and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgery, 258(6), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182988d59

2. Turan, A., Mascha, E., Roberman, D., Turner, P. L., You, J., Kurz, A., Sessler, D. I., Saager, L. (2011). Smoking and Perioperative Outcomes. Anesthesiology, 114(4), 837-846. https://doi.org/10.1098/ALN.0b013e318210f560

3. Rusy, D., Honkanen, A., Landrigan-Ossar, M. F., Chatterjee, D., Schwartz, L., Lalwani, K., Dollar, J., Clark, R., Diaz, C. D., Deutsch, N., Warner, D. O., Soriano, S. G., (2021). Vaping and E-Cigarette Use in Children and Adolescents: Implications on Perioperative Care from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Pediatric Anesthesia, Society for Pediatric Anesthesia, and American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 133(3), 562-568. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005519

4. Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of internal medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

5. Fiore, M. C., Jaén, C. R., Baker, T. B., et al. (2008). Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf

6. Government of British Columbia (n.d.). Smoking Cessation Program – information for health professionals. Retrieved October 18, 2024, from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/pharmacare/pharmacies/smoking-cessation-program-for-health-professionals

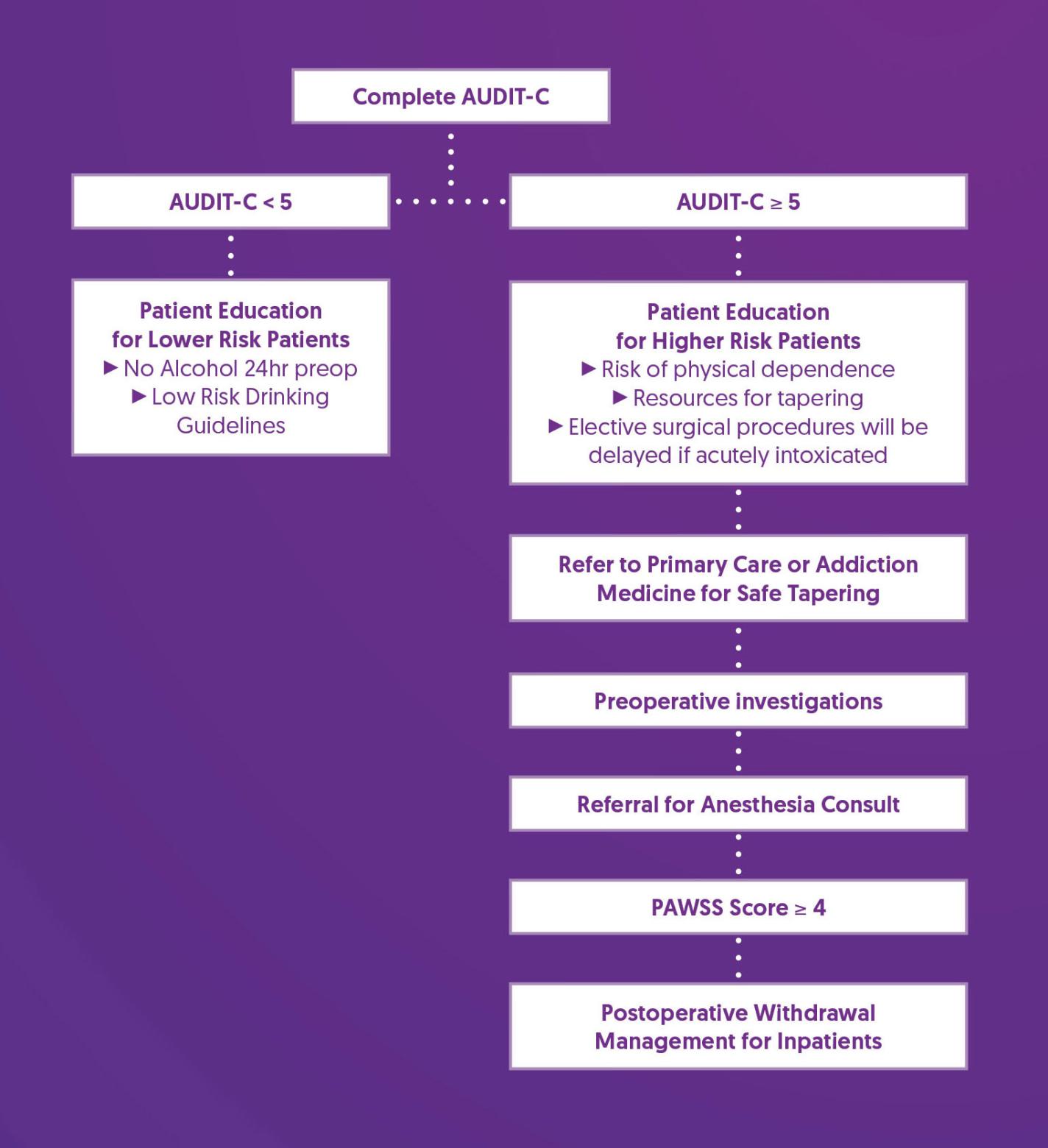

Substance Use - Alcohol

Preoperative alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of postoperative morbidity, infections, wound complications, pulmonary complications, prolonged hospital length of stay, and admission to intensive care. (1) Screening for alcohol misuse prior to elective surgery allows for further screening for health complications, planning for those at risk of complicated withdrawal, and offering resources for safe tapering preoperatively in those patients who are motivated to do so.

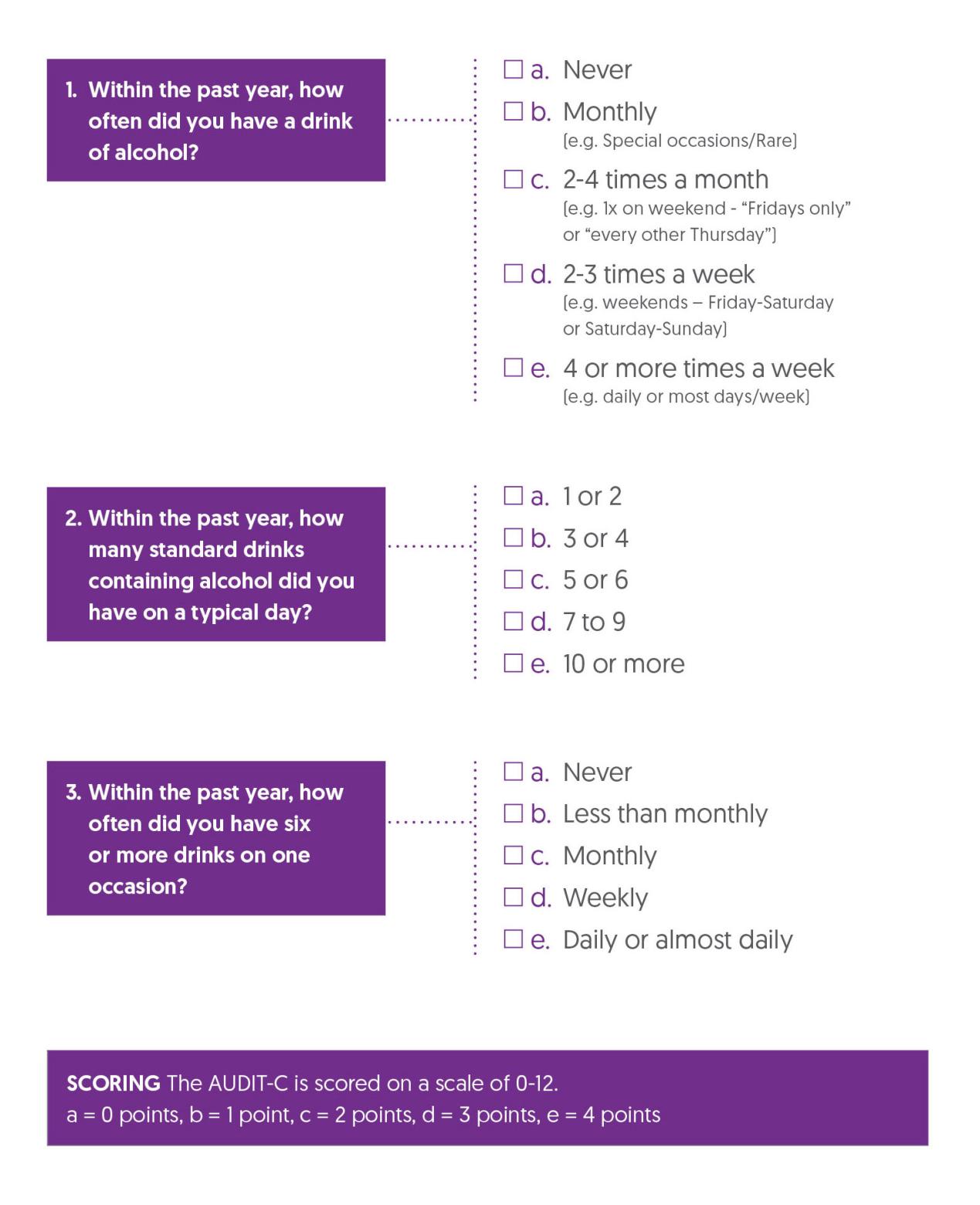

Screening Tools

The AUDIT-C is an effective and validated 3-question screen for severity of alcohol misuse that is based on the 10-question AUDIT questionnaire. (2)

AUDIT-C Questionnaire

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education for Lower Risk Patients (AUDIT-C < 5) |

|

| Patient Education for Higher Risk Patients (AUDIT-C >= 5) |

|

| Referral for Safe Tapering |

|

| Preoperative Investigations |

|

| Referral for Anesthesia Consult |

|

| PAWSS Score |

|

| Postoperative Withdrawal Management for Inpatients |

|

References

1. Eliasen, M., Grønkjær, M., Skov-Ettrup, L. S., Mikkelsen, S. S., Becker, U., Tolstrup, J. S., & Flensborg-Madsen, T. (2013). Preoperative alcohol consumption and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgery, 258(6), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182988d59

2. Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of internal medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

Substance Use - Cannabis

Cannabis (marijuana) use may lead to increased anesthetic requirements, postoperative pain, opioid use after surgery, and nausea and vomiting. (1-3) Smoking cannabis increases the risk of pulmonary complications, cardiovascular complications (including postoperative myocardial infarction), and in-hospital mortality; it may also increase airway irritation, carboxyhemoglobin, and reduce oxygen-carrying capacity, similar to conventional cigarette smoking. (3-5)

Screening Tools

Cannabis Screening Questions:

Do you use Cannabis? If Yes:

- How often?

- How much do you use?

- How are you using it? (e.g., smoking, vaping, tincture/oil, edibles, cream)

- Have you ever had symptoms like headaches, anxiety, poor sleep, or stomach pain when you stopped using cannabis for a day or two (Cannabis Withdrawal Syndrome)?

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Recommend Self Taper |

|

| Referral for Supported Taper |

|

| Referral for Anesthesia Consult |

|

| Provide Education on Cannabis Withdrawal Syndrome |

|

References

1. Ladha, K. S., McLaren-Blades, A., Goel, A., Buys, M. J., Farquhar-Smith, P., Haroutounian, S., Kotteeswaran, Y., Kwofie, K., Le Foll, B., Lightfoot, N. J., Loiselle, J., Mace, H., Nicholls, J., Regev, A., Rosseland, L. A., Shanthanna, H., Sinha, A., Sutherland, A., Tanguay, R., Yafai, S., … Clarke, H. (2021). Perioperative Pain and Addiction Interdisciplinary Network (PAIN): consensus recommendations for perioperative management of cannabis and cannabinoid-based medicine users by a modified Delphi process. British journal of anaesthesia, 126(1), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.09.026

2. Shah, S., Schwenk, E. S., Sondekoppam, R. V., Clarke, H., Zakowski, M., Rzasa-Lynn, R. S., Yeung, B., Nicholson, K., Schwartz, G., Hooten, W. M., Wallace, M., Viscusi, E. R., & Narouze, S. (2023). ASRA Pain Medicine consensus guidelines on the management of the perioperative patient on cannabis and cannabinoids. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine, 48(3), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2022-104013

3. Echeverria-Villalobos, M., Todeschini, A. B., Stoicea, N., Fiorda-Diaz, J., Weaver, T., & Bergese, S. D. (2019). Perioperative care of cannabis users: A comprehensive review of pharmacological and anesthetic considerations. Journal of clinical anesthesia, 57, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2019.03.011

4. Tetrault, J. M., Crothers, K., Moore, B. A., Mehra, R., Concato, J., & Fiellin, D. A. (2007). Effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications: a systematic review. Archives of internal medicine, 167(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.3.221

5. Jeffers, A. M., Glantz, S., Byers, A. L., & Keyhani, S. (2024). Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults. Journal of the American Heart Association, 13(5), e030178. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.030178

6. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2017). 10 Ways to Reduce Risks to Your Health When Using Cannabis. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdfs---reports-and-books---research/canadas-lower-risk-guidelines-cannabis-pdf.pdf

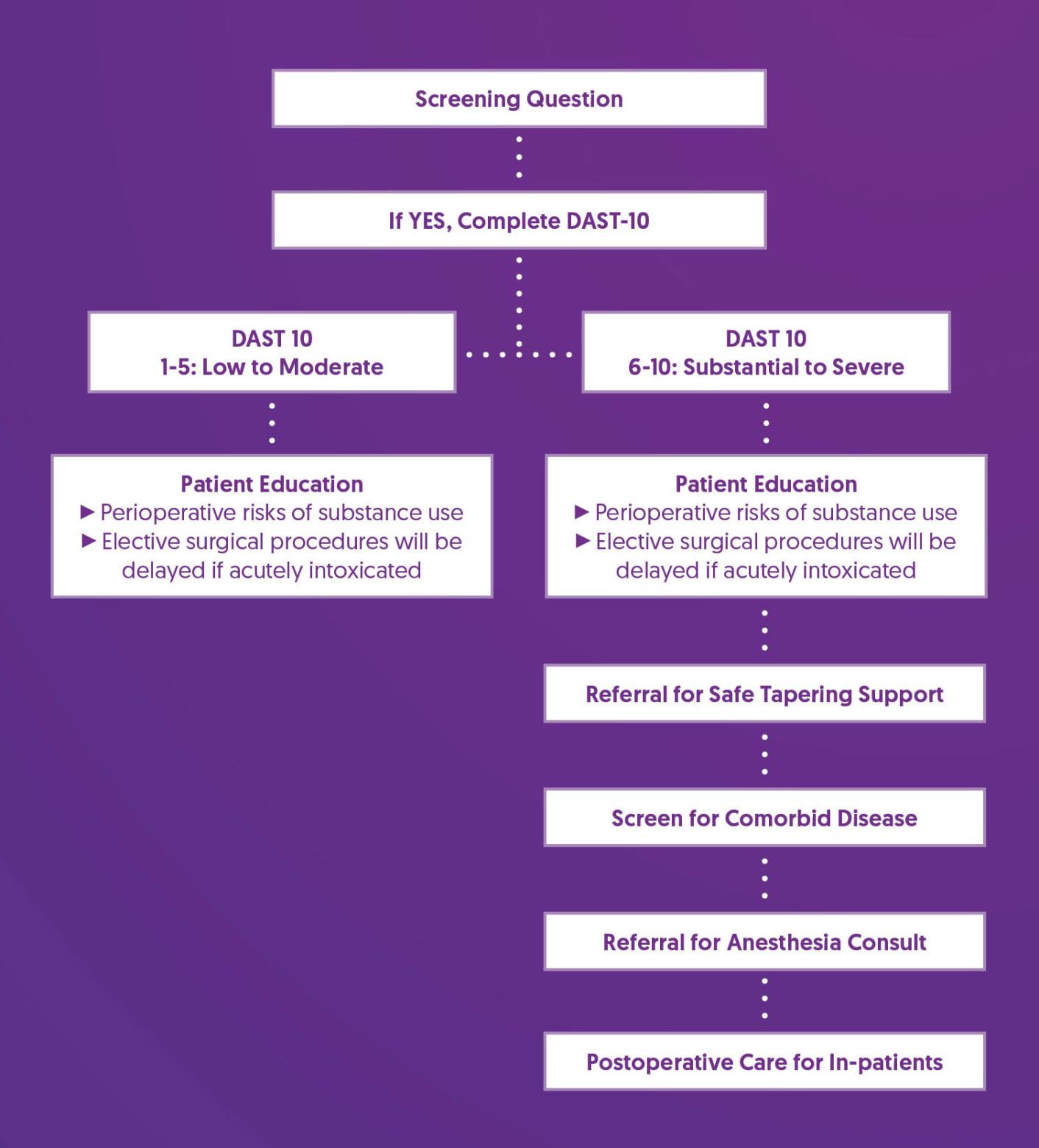

Substance Use - Illicit Substances

Substance use is associated with increased postoperative complications, prolonged hospital length of stay, and increased healthcare costs. (1-4) Acute intoxication and chronic use have implications for perioperative care. (5)

Additional challenges depend on the severity and type of substance(s) used, as well as other factors that may be associated with substance use, including experiencing homelessness or mental illness. Collaboration with community providers is important, especially for patients being treated for opioid use disorder.

Screening Tools

Screening Questions:

- In the last 12 months, have you used drugs other than those required for medical reasons? (not including alcohol or cannabis)

- If yes, characterize drug use (drug, dose, frequency, and route of administration)

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) is a validated 10-item brief screening tool that assesses drug use (excluding alcohol and tobacco), in the past 12 months and gives a score of the degree of problems related to drug use and misuse. (6,7) This allows preoperative interventions to target those patients with substantial or severe problems related to drug abuse.

Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10)

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Referral for Safe Tapering Support |

|

| Screen for Comorbid Disease |

|

| Referral for Anesthesia Consult |

|

| Postoperative Care for Inpatients |

|

References

1. Kulshrestha, S., Bunn, C., Gonzalez, R., Afshar, M., Luchette, F. A., & Baker, M. S. (2021). Unhealthy alcohol and drug use is associated with an increased length of stay and hospital cost in patients undergoing major upper gastrointestinal and pancreatic oncologic resections. Surgery, 169(3), 636–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2020.07.059

2. Venishetty, N., Nguyen, I., Sohn, G., Bhalla, S., Mounasamy, V., & Sambandam, S. (2023). The effect of cocaine on patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Journal of orthopaedics, 43, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2023.07.029

3. Best, M. J., Buller, L. T., Klika, A. K., & Barsoum, W. K. (2015). Outcomes Following Primary Total Hip or Knee Arthroplasty in Substance Misusers. The Journal of arthroplasty, 30(7), 1137–1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.052

4. Raso, J., Althoff, A., Brunette, C., Kamalapathy, P., Arney, M., & Werner, B. C. (2023). Preoperative Substance Use Disorder Is Associated With an Increase in 90-Day Postoperative Complications, 1-Year Revisions and Conversion to Arthroplasty Following Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair: Substance Use Disorder on the Rise. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery: official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association, 39(6), 1386–1393.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2022.12.026

5. Jimenez Ruiz, F., Warner, N. S., Acampora, G., Coleman, J. R., & Kohan, L. (2023). Substance Use Disorders: Basic Overview for the Anesthesiologist. Anesthesia and analgesia, 137(3), 508–520. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006281

6. Yudko, E., Lozhkina, O., & Fouts, A. (2007). A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 32(2), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002

7. Gavin, D. R., Ross, H. E., & Skinner, H. A. (1989). Diagnostic validity of the drug abuse screening test in the assessment of DSM-III drug disorders. British journal of addiction, 84(3), 301–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03463.x

8. Gould, R., Lindenbaum, L., & Rogers, K., (2024). Anesthesia for patients with substance use disorder or acute intoxication. UpToDate. Retrieved Aug 24, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/anesthesia-for-patients-with-substance-use-disorder-or-acute-intoxication

Support After Surgery

Making arrangements in advance to have adequate support at home can help patients return home after surgery as soon as it is appropriate and avoid delays to discharge. (1,2) Traditional criteria for discharge following day surgery includes the presence of a capable adult care-giver for 24 hours postoperatively.

Screening Tools

Screening Questions:

- Do you have someone that can help you during your recovery after surgery if necessary?

- Do you have someone who can take over your caregiving responsibilities while you recover from surgery (e.g.,vulnerable adults, children, or pets)?

Prehabilitation and Optimization Algorithm

Prehabilitation and Optimization Recommendations

| Patient Education |

|

| Provide resources for those with no support |

|

References

1. Kay, A. B., Ponzio, D. Y., Bell, C. D., Orozco, F., Post, Z. D., Duque, A., & Ong, A. C. (2022). Predictors of Successful Early Discharge for Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in Octogenarians. HSS journal : the musculoskeletal journal of Hospital for Special Surgery, 18(3), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/15563316211030631

2. Zhang, Z., & Tumin, D. (2019). Expected social support and recovery of functional status after heart surgery. Disability and rehabilitation, 42(8), 1167–1172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1518492